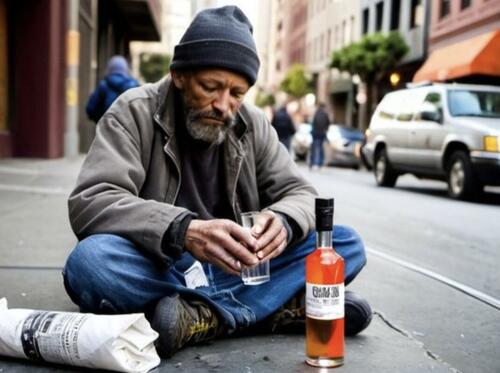

San Francisco Ends $5M-A-Year Program That Supplied Alcohol To Homeless Addicts

Sigh. It's not parody. It's San Francisco. The city is shutting down a controversial program that used millions in taxpayer funds to provide alcohol to homeless residents struggling with addiction, according to the NY Post.

Mayor Daniel Lurie said the city will end the Managed Alcohol Program, which cost about $5 million each year and began during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“For years, San Francisco was spending $5 million a year to provide alcohol to people who were struggling with homelessness and addiction — it doesn’t make sense, and we’re ending it,” Lurie told The California Post.

The program was launched in April 2020, when the city placed unhoused residents in hotels during lockdowns. Medical staff supplied controlled amounts of beer and liquor to prevent dangerous withdrawal symptoms while stores and bars were closed. Although intended as a temporary measure, it continued for nearly six years.

During its operation, the program served only 55 people, translating to an average cost of roughly $454,000 per client.

Now, Lurie says the city has fully pulled its support.

“We have ended every city contract for that program,” he said.

Community Forward, the nonprofit that managed the initiative in recent years, confirmed that the city has terminated its funding. Financial records show the group received millions in public money, much of it spent on staff salaries.

San Francisco’s program was the first of its kind in the United States, modeled loosely on similar efforts in Canada. Unlike other harm-reduction policies, such as needle exchanges, MAP directly supplied alcohol to people already dependent on it.

Since taking office last year, Lurie has moved away from long-standing harm-reduction policies. He has also ended the distribution of drug-use equipment and pushed for stricter enforcement of street drug activity.

“Under my administration, we made San Francisco a recovery-first city and ended the practice of handing out fentanyl smoking supplies so people couldn’t kill themselves on our streets,” Lurie said.

“We have work to do, but we have transformed the city’s response, and we are breaking the cycles of addiction, homelessness and government failure that have let down San Franciscans for too long.”

Last year, he warned open-air drug markets that enforcement would increase.

“If you do drugs on our streets, you will be arrested,” Lurie said. “And instead of sending you back out in crisis, we will give you a chance to stabilize and enter recovery.”

The Post writes that recovery advocates welcomed the decision to end MAP. Tom Wolf, a former homeless addict who now works in outreach, said the program wasted public funds.

“They [were] wasting our money just paying people to keep using the drug that they’re hopelessly addicted to,” Wolf said.

He also criticized how harm reduction has evolved.

“Harm reduction itself is part of the overall social justice framework,” he said, adding that it has shifted from preventing disease to “supporting drug users.”

Steve Adami, head of the Salvation Army’s recovery-focused program in San Francisco, said the city is now rethinking decades of policy.

“Under Mayor Lurie, they have reassessed the outcomes of those models,” Adami said. “That we are a recovery-first city. He’s made a significant investment into abstinence-based and recovery-focused services.”

In May, Lurie signed the Recovery First Act, signaling a shift toward abstinence and treatment-based approaches.

Despite the changes, major challenges remain. San Francisco has limited detox capacity, with only about 68 beds for thousands of people who cycle through homelessness each year. Many residents seeking help still face long waits for treatment.

The end of the alcohol program reflects the mayor’s broader effort to reverse years of permissive policies as he tries to address addiction, homelessness, and the decline of the city’s downtown core.