War Finance

Americans, Beijing, Washington and the Fed are reacting to developments in the trade war as they come. But these reactions are best understood as responses to an emerging world order, in particular one where the financial flows of the previous world order are, or soon will be, no longer reliable due to geopolitical fragmentation. This sets the stage for Zoltan Pozsar's War Finance, which is already underway, to be fully realized.

War Finance includes but goes beyond the Fed's balance sheet policy (QE) and the Treasury's fiscal policy (stimulus) - it encompasses structural changes in how capital is allocated, how reserves are managed and when intervention in markets is due. Its focus is less on supporting a global financial empire and more about securing the onshore credit needs of private industry, be it semiconductor lithography, energy production or steel manufacturing.

In this regime, the lines between fiscal and monetary policy begin to blur. War Finance would call for the Fed and the Treasury to officially fuse into a single framework, where policy is most powerful, which was the case during World War II when the former explicitly supported the latter.

The US is not currently outfitted for War Finance, as fiscal and monetary policy continue to diverge due to obvious political differences, but the Trump administration clearly recognizes the necessity. It will take an implosion before both recognize with absolute clarity that the old paradigm can no longer be relied on, and with that implosion will follow better choreography, as it always does in a crisis.

Following last week's Liberation Day announcement of official reciprocal tariff rates, I couldn't help but notice a question that seemed to linger everywhere: what is the Fed supposed to do?

If you're somewhat familiar with what I write about, you'll probably notice how I rarely think about the "what should they do" and instead focus on the "what will they do." Should the Fed have made four rate cuts over three meetings last year? Probably not. But, by early summer, it soon became clear that they were going to anyway.

That said, what will the Fed do? Cut? Pause?? Hike???

Whatever it is, surely, it will be meaningful.

Zerohedge echoed this on X, asking whether the stimulus will first come from rate cuts (Fed) or fiscal expansion (Treasury).

Fiscal or monetary stimulus first?

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) April 2, 2025

There's at least one person in high finance whose reputation I believe will reach legendary status, if it hasn't already, as the Trump administration gets under way. After a couple years of mockery for holding such bold and contrarian views, many of the things he wrote about are finally unfolding: tariffs, reshoring, FX reserve managers at Asian central banks buying gold, US sovereign wealth funds, stockpiling commodities & rare earth minerals... the list goes on...

... but that's only a fraction of the list. Each of these things are part of a bigger theme. And understanding what that theme is will give the current environment much better context.

He had been advising Treasury secretary Scott Bessent in the months leading up to Trump's November election victory, and probably has been since, so it should come as no surprise that the new administration appears to be embracing what he warned the financial world of years ago, namely about a reversal in global financial flows as a result of geopolitical fragmentation. At times I've personally doubted him and even questioned his credibility, but his calls appear to be growing more and more relevant each day, so it would seem like a good time to get familiar with what he's written, if you aren't already.

In fact, I suggested as much to the zerohedge audience last week.

Seems like a good time for a refresher on Zoltan's War Finance, imo...https://t.co/d7gHxN1kdu

— Mike (@DeathTaxesandQE) April 2, 2025

In the second half of 2022, while still employed by Credit Suisse as an interest rate strategist, Zoltan Pozsar published his famous War series:

- War and Interest Rates, July 31, 2022

- War and Industrial Policy, August 23, 2022

- War and Commodity Encumbrance, December 26, 2022

- War and Currency Statecraft, December 28, 2022

- War and Peace, January 5, 2023

By "war", Pozsar speaks of full-spectrum geopolitical rivalry - a cold war fought on economic, financial, technological, and hard resource fronts between Great Powers. In his framework, war is as much about semiconductors, deep sea cables, swap line access and rare earth minerals as it is about troops, missiles, ships and military hardware. This cold war, however, is much different from the cold war of the 20th century as, this time, each adversary has incredible financial infrastructure that they aren't reluctant to weaponize. Therefore, financial policy must be outfitted to serve national security goals.

Pozsar's use of the phrase War Finance dates before 2022, and is best described as a response to a shift, what he calls a response to a crisis: a slow motion financial divorce between the global South and the West.

War cuts new financial channels, he says:

What are G7 policymakers, rates traders, and strategists to do when threats to the unipolar world order are coming from every angle. They should definitely not ignore the threats, but they still do. How could they not? For two generations, we did not have to discount geopolitical risks. Since the end of WWII, the only Great Power conflict investors really had to deal with was the Cold War, and since the conclusion of the Cold War, the world enjoyed a unipolar “moment” – the U.S. was the undisputed hegemon, globalization was the economic order, and the U.S. dollar was the currency of choice. But today, geopolitics has reared its ugly head again: for the first time since WWII, there is a formidable challenger to the existing world order, and for the first time in its young history, the U.S. is facing off against an economically equal or, by some measures, superior adversary.

The American Paradigm

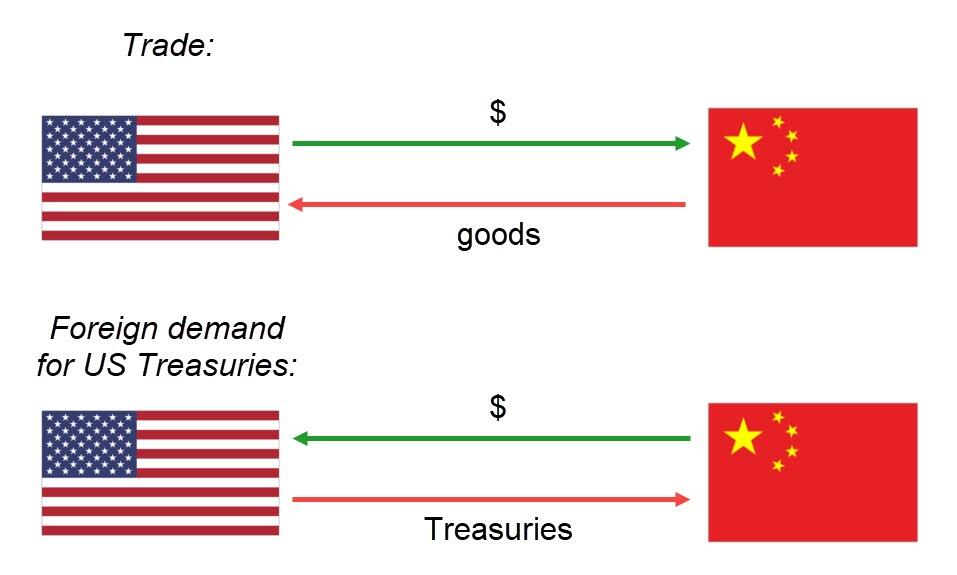

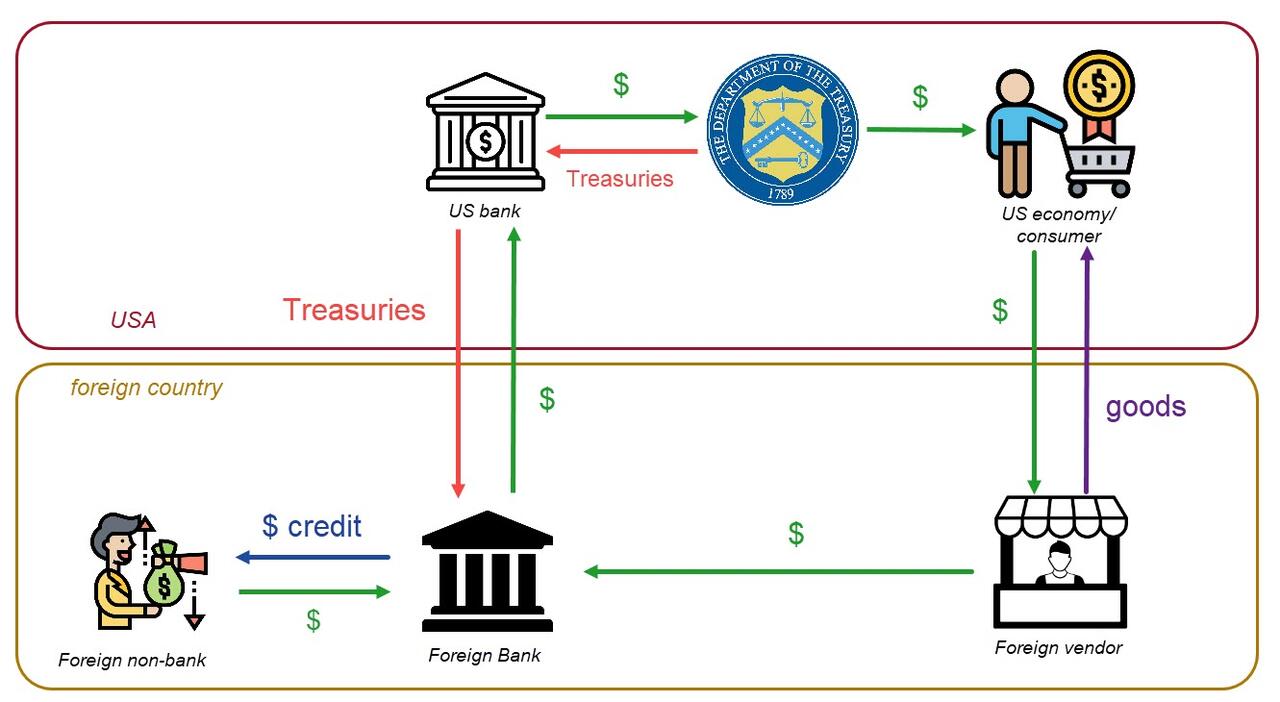

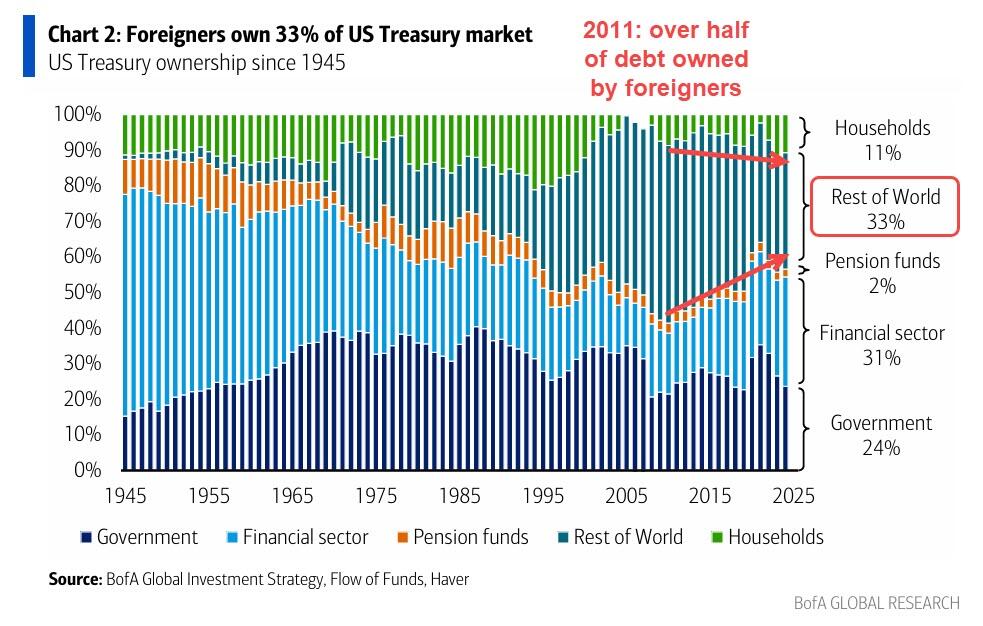

For decades, we had an undisputed, unipolar world order - a global system where foreign nations running a trade surplus would trade goods for dollars and recycle those earned dollars into Treasuries, giving them a parking spot in the US financial system that backstopped their banks. Treasuries could easily be monetized (sold) for cash or pledged as collateral for dollar loans in the repo market. In some ways, foreign banking systems came to rely on this setup even more than the US banking system did.

The classic example is of the petrodollar, but today it's become a much bigger system encompassing more goods than simply oil.

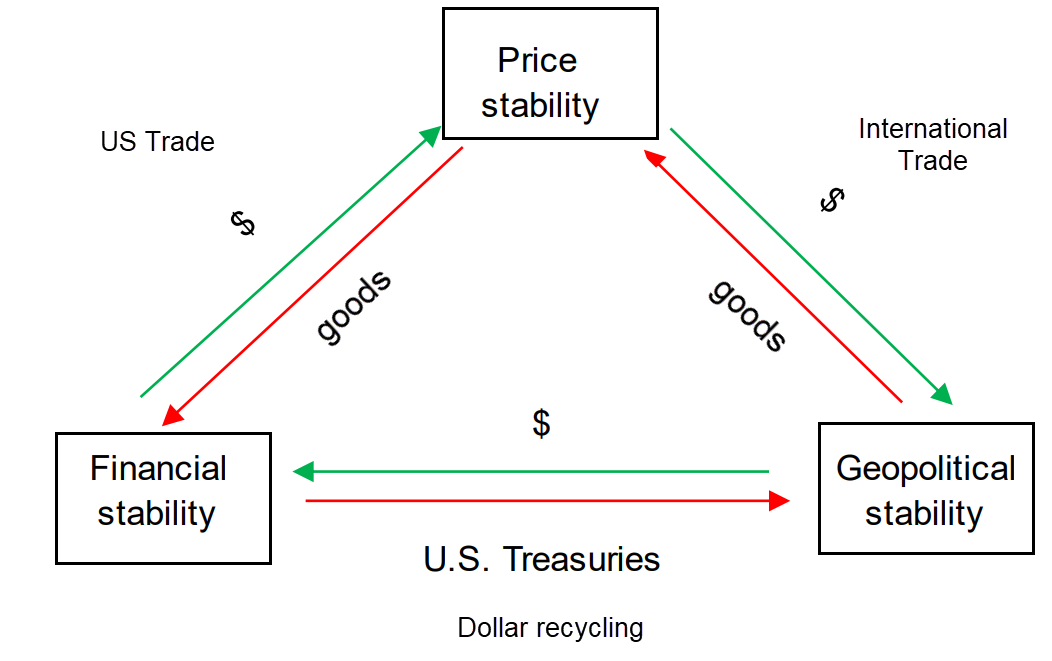

For a while, it was a "heavenly match": offshore nations would be able to upscale their economies and their firms could easily obtain dollar credit (including dollar credit from non-US banks), all while backstopping their banking system. Having a foothold in the US financial system also afforded them a spot under the American security umbrella. Across the ocean, this meant the US would be able to finance and support its "exorbitant privilege" that relied on ample demand for Treasuries. Ample demand for Treasuries and supply chain security meant inflation was reasonable. China, and any trade partner, dutifully recycling their earnings back into our debt claims was the bedrock of the calm, low inflation world.

All sides were entangled commercially as well as financially, and as the old wisdom goes, if we trade, everyone benefits and so we won’t fight. But like in any marriage, that’s true only if there is harmony. Harmony is built on trust, and occasional disagreements can only be resolved peacefully provided there is trust.

When trust is gone, everything is gone, which, to quote Zoltan, is "a scary conclusion."

Pozsar's instinct was that the seizure of Russia's FX reserves in response to the invasion of Ukraine meant this trust had broken, ended the "heavenly match" and thus signaled those foreign capital flows, one of the pillars that kept the world stable, would necessarily begin to go into reverse. It wasn't necessarily that the seizure of Russian FX reserves caused this trust to break, but was, at least, a manifestation that it had already been broken.

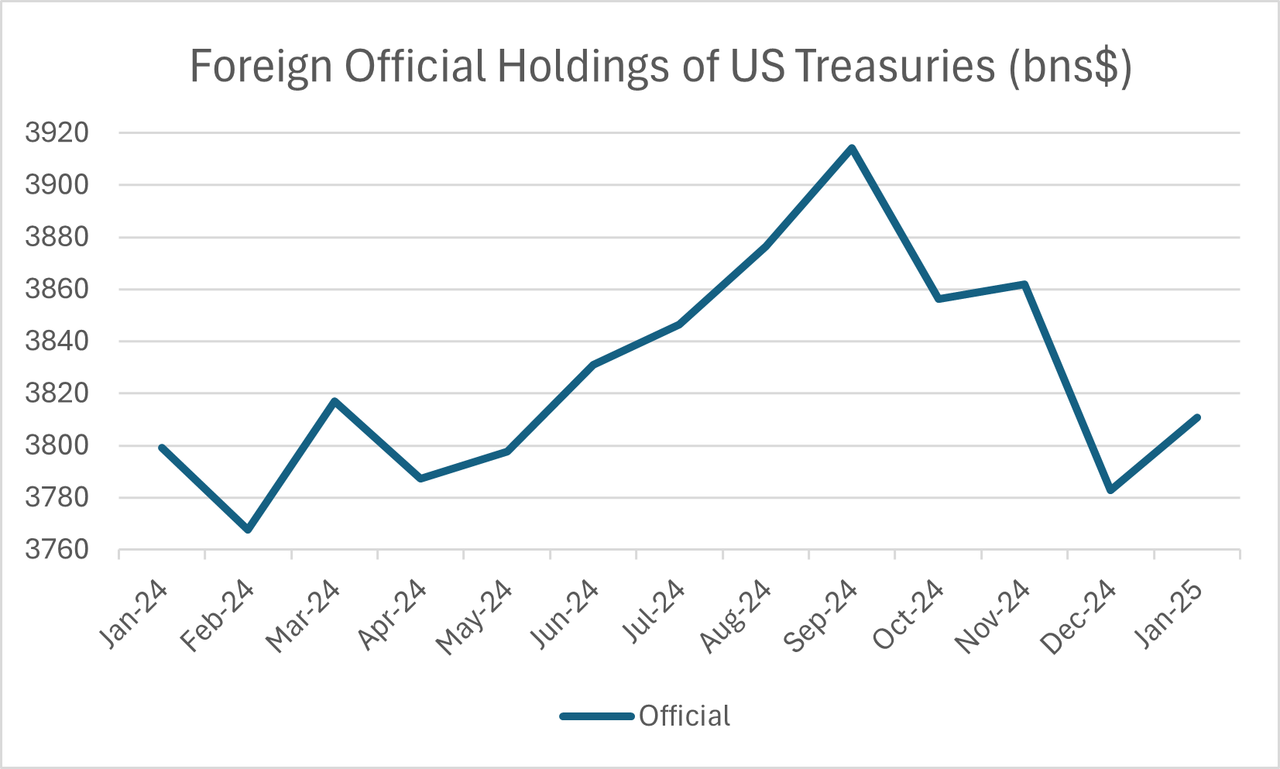

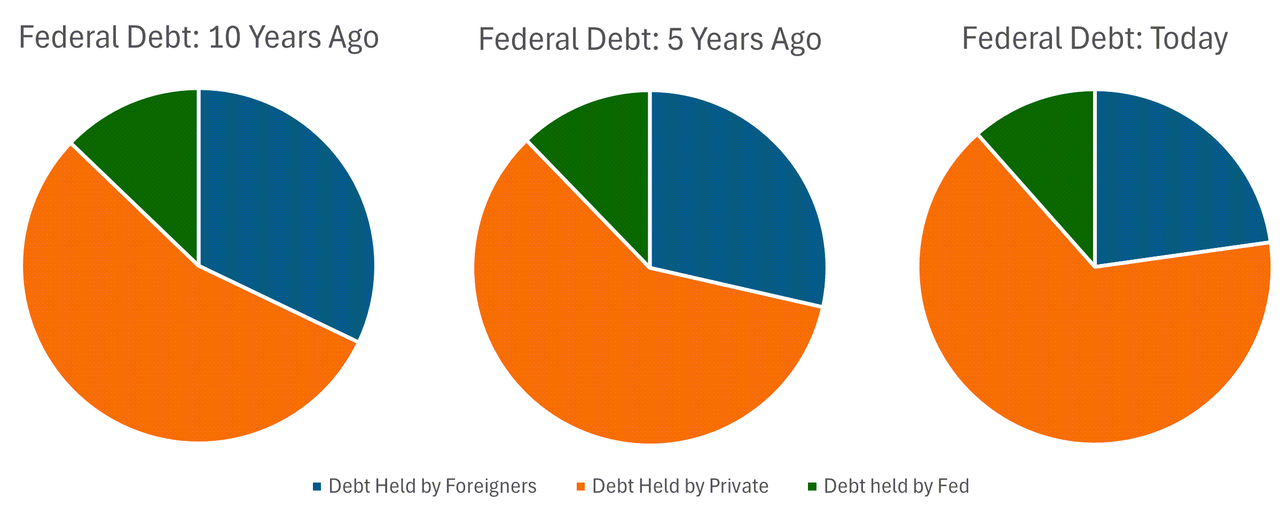

He would say that, one of the pillars in the visual example above, foreign demand for US Treasuries, slowed long before tariffs came in to slow the export of dollars. In that sense, tariffs are catching up with this new paradigm. The US was still running historically-large trade deficits over the last year, but it was not met with foreign official sector accumulation of Treasuries, or at least certainly not to any reciprocal extent. In a financially unipolar world, this would not happen:

As I showed last August, the gross uptick in foreign US Treasury demand over the last year came from the non-official sector (which means any financial entity that's not a government or central bank) on the margin. Many of which were probably foreign hedge funds, since foreign pensions, banks and life insurers would FX-hedge their Treasuries. Those foreign non-official bond purchases were basically speculative, not funded with the dollars recycled from trade surplus.

You would not realize that this is what's going on just by looking at the results for Treasury auctions: one day can have "stellar" foreign demand, and the next day you might see the weakest in years. I mean, literally, the next day...:

Auctions are pretty technical (here's a good piece on the nitty gritty), and reading too deeply into the individual results can be misleading. Countries will buy and sell Treasuries to weaken and strengthen their FX, respectively, like what the Japanese did repeatedly last year as they defended a weaker yen. They could buy something else, but most assets are just not liquid enough for FX interventions, and liquidity is crucial if you want to avoid realizing big losses unnecessarily.

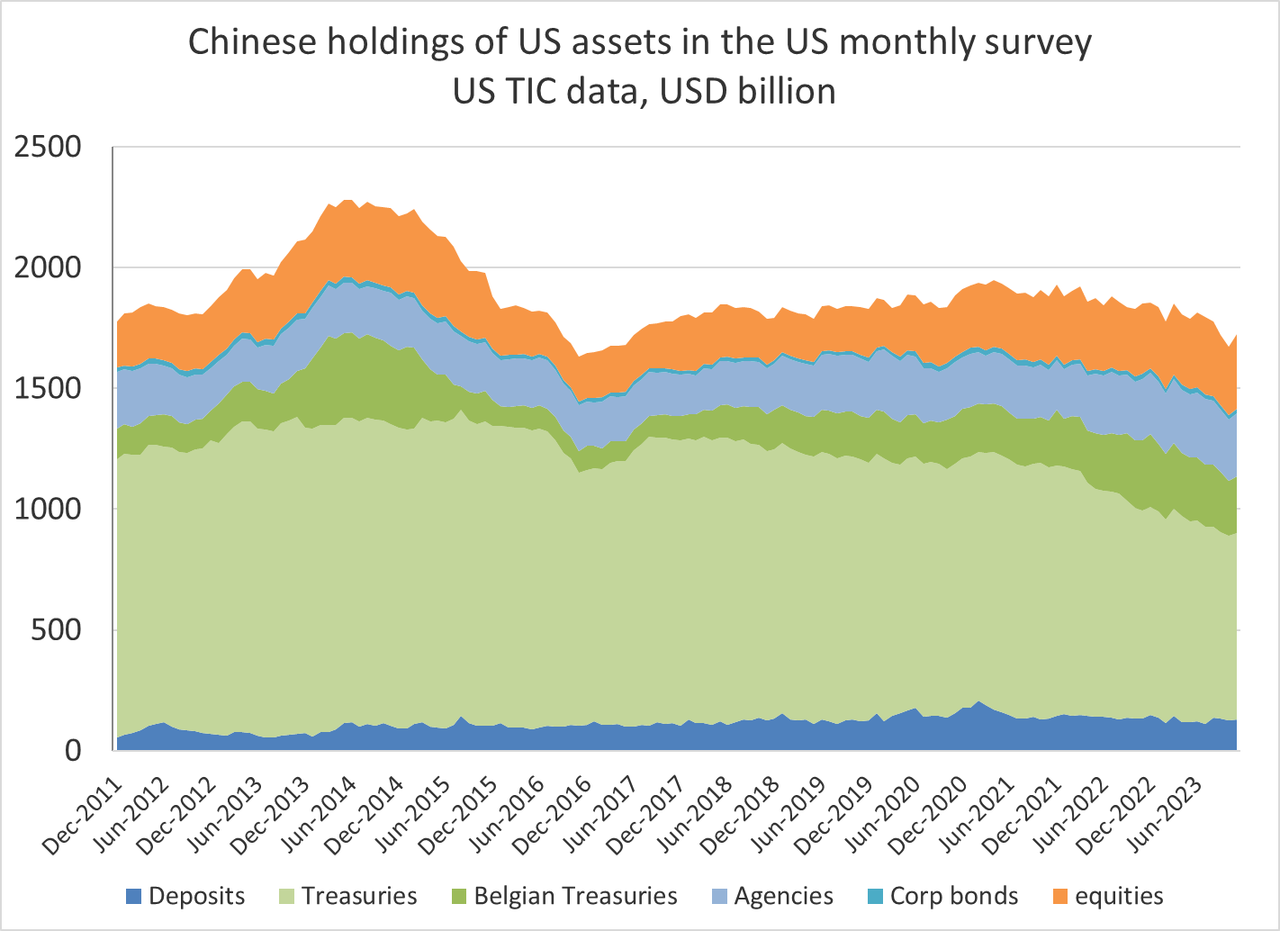

In any case, it's hard to make sense of this disconnect - after all, if a foreign nation is running a large trade surplus with the US, but isn't recycling that surplus back into Treasuries, where are those dollars going? Sticking with the example of China, Brad Setser has showed that total Chinese dollar reserves are virtually unchanged, but its composition includes less Treasuries. Instead, those dollars are recycled into other USD assets, like mortgage-backed securities (Agency MBS) and equities:

As Pozsar said in August 2022:

It makes absolutely and categorically no logical sense for (China) to roll their investments in G7 debt claims. Not just because of what happened to Russia’s FX reserves, but also because rolling a $1 trillion portfolio of U.S. Treasury securities means that you will fund the West’s effort against the East.

Unfortunately, most of Pozsar's audience at the time seemed to interpret that comment as "China has no use for dollars... period!" The fact that it's not Treasuries, however, is what's important: China can invest its USD surplus into equities, Agencies, corporate bonds, deposits or anything else for the sake of argument, but only one asset will finance the US government. There's only one asset that supports the Treasury's blank check to borrow ad infinitum. There's only one asset the Fed, as an institution, cares about. And there's only one asset which, when it begins to tremble, will make the rest of the world feel unsteady such that even the President has to get involved.

To paraphrase Pozsar, when all is said and done a lack of Treasury demand is still a lack of Treasury demand.

Reading between the lines of Pozsar's War series, everything he called for becomes much clearer. If foreign trade surplus nations would not support the exorbitant privilege of the dollar by recycling excess US savings (dollars they earn through trade) into Treasuries - a bold call he predicted years ago would emerge - then the US is literally and quite blatantly being ripped off.

This was my eureka moment where I realized "well of course the US needs to tariff its imports!", and surely that was Pozsar's thinking, too. Capital abroad is not doing its "job", so it must be repatriated. Domestic capital must plug the holes that foreign capital was expected to.

Keep in mind that this is just one of several credible motives for tariffs. Along with that, reshoring supply chains away from China, an adversary in this cold war, is crucial if the US wants to remain militarily credible. To put it one way, imagine how reckless it would've been had the US imported aluminum, titanium and rocket tech from the Soviet Union during the 1960s!

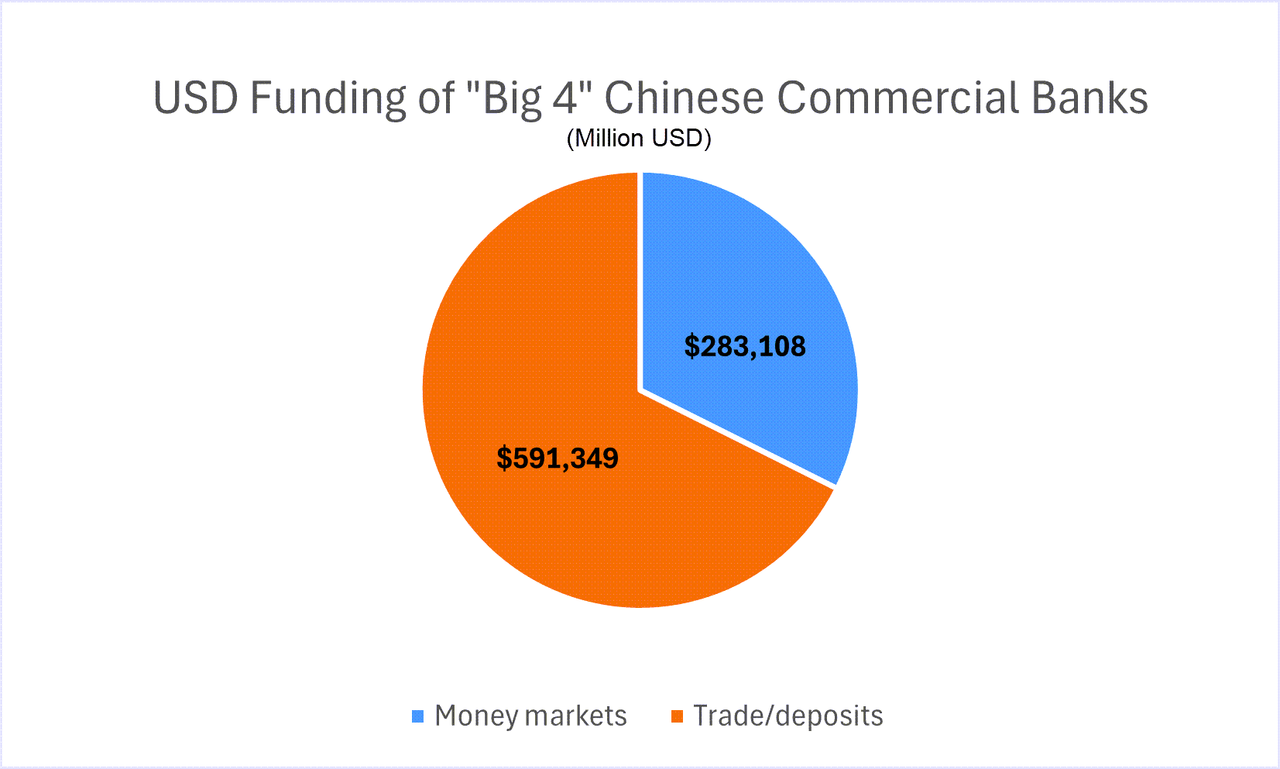

And, like I said on April 1st, the tariff wall appears to target China in an attempt to hurt their dollar funding more immediately than the rest of the world. If there's any tariffs at all, be it reciprocal tariffs, Section 232 tariffs or existing tariffs that have been in place for a while, China is going to face them.

Hence why, as of April 9th, Trump paused reciprocal tariffs on virtually every trading partner...

...except China.

Trump is hiking tariffs on China to 125%, authorizes a 90 day tariff pause on everyone else pic.twitter.com/BzqhbKvXi5

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) April 9, 2025

Financial Repression

So here we have a system where nations won't recycle their trade surplus, earned by selling to Americans, back into US Treasuries and thus won't commit to financing US hegemony. This is a crisis - the economic front of a cold war. With foreign capital no longer keeping its side of the bargain, War Finance responds by picking up the slack in support of domestic industry and capital.

Supporting domestic industry is a matter of tariffs - making domestic goods more price-competitive than imported goods - and fiscally sponsored industrial policy. That doesn't necessarily mean subsidizing the black hole of government projects, but could be tax breaks, legislation or anything that supports said industries.

To quote Pozsar;

Wars cannot be fought with supply chains that crisscross a globalized world, where production happens on faraway, little islands in the South China Sea, from where chips can be transported only if airspaces and straits remain open. Global supply chains work only in peacetime, but not when the world is at war, be it a hot war or an economic war.

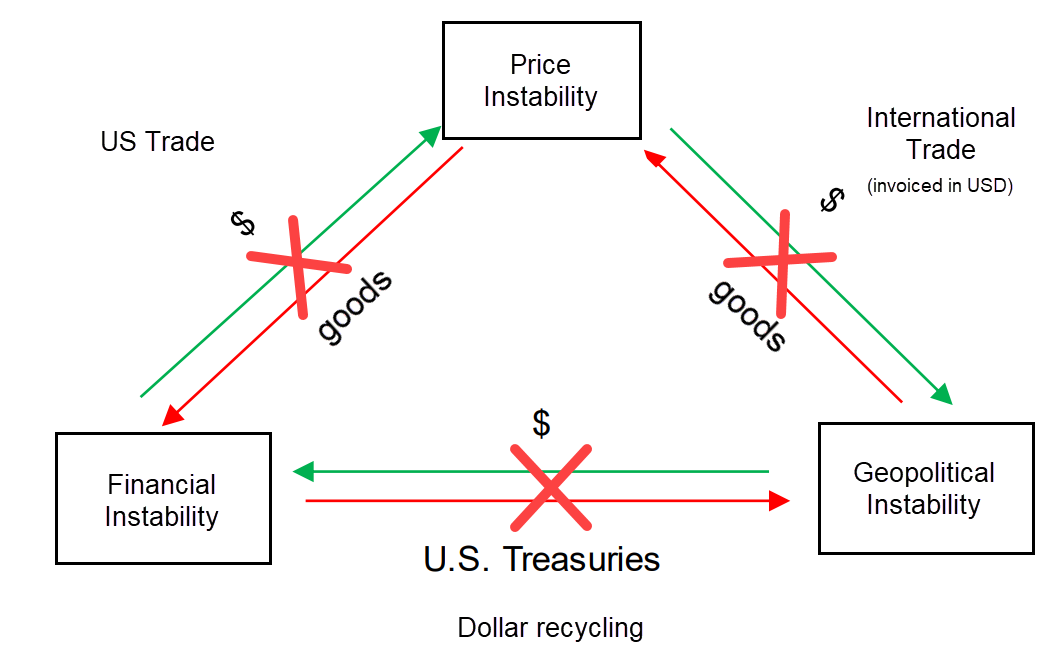

The result of this war is geopolitical, financial and price instability. When one of these pillars break (like it did after Covid, which the G7 seizure of Russia's FX reserves signaled), the others begin to follow...

... creating instability on every front - geopolitical, financial, and price - or, simply, inflation.

Supporting domestic capital, on the other hand, is a different beast altogether. One that, especially since 2020, is not very popular as it means stimulus.

"So keep an open mind, or get financially repressed" is a relatively well-known Pozsar quote. What he's saying is that by failing to question the prevailing assumptions and think outside the traditional models, that I just described, you will miss the regime shifts and be left stuck in assets (Treasuries) or frameworks (dollar recycling from trade surplus nations) that are no longer relevant. As a result, you will underperform, and lose your purchasing power.

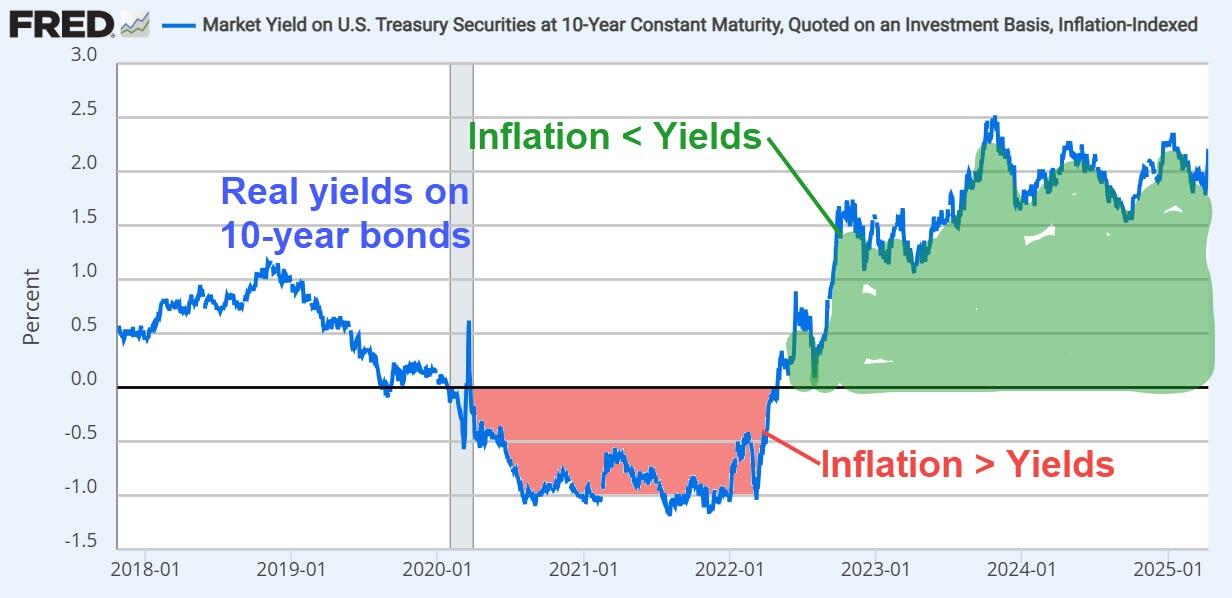

Pozsar's adage was speaking directly to bond holders, warning of a coming negative real interest rates regime, a.k.a. financial repression where Treasuries yield less than inflation. Again, in the Pax Americana paradigm, this isn't *supposed* to happen: interest rates are *supposed* to account for inflation. You don't buy a bond for a 2% yield if inflation is thrice that, because you'll lose the difference: you'd be financially repressed. The bond market is *supposed* to price inflation with positive real yields, nominal yields above inflation, unless the Fed is buying in the midst of a depression.

Letting the bond market price yields could threaten the government's ability to support industry.

Hence, real yields may be negative because, hell or high water, circumstance demands it. So keep an open mind to that possibility, or fall victim to financial repression where your fixed-income returns (ex., with your pension) are erased by inflation.

Yield Curve Control

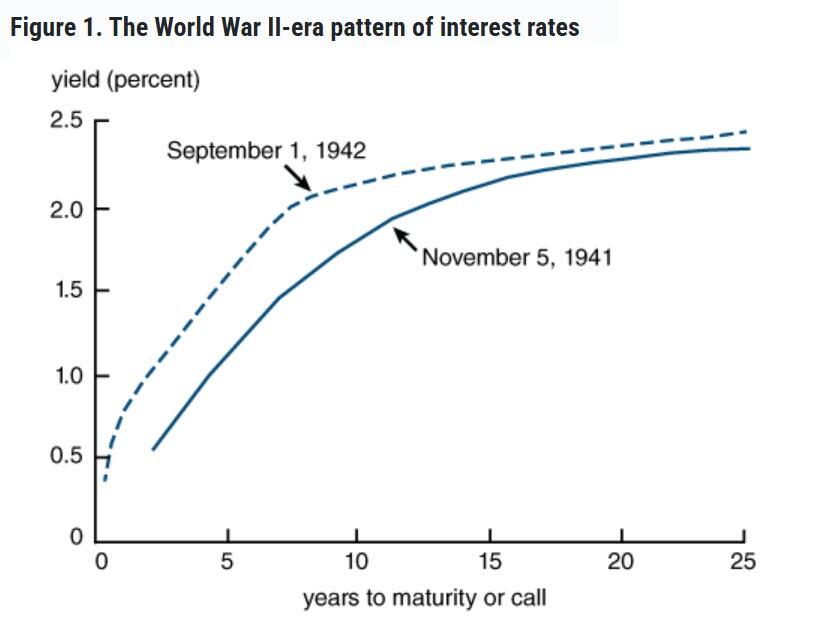

A concerted shift to War Finance would see fiscal policy (Treasury spending) and monetary policy (what the Fed does with interest rates and its balance sheet) fuse, since one channel alone would not suffice. One of the most classic examples of this link is a Yield Curve Control (YCC) policy. Few people know the history, but it won't be America's first foray into YCC.

By the time the US entered into World War II, interest rates were set in consultation with the Treasury, who insisted that the Fed cap rates low. The Fed obliged, and operated a framework where short-term rates were set at 0.375% and longer-term yields were capped at 2.5%. While this began under the emergency pretense of global war, it continued for seven years after the war.

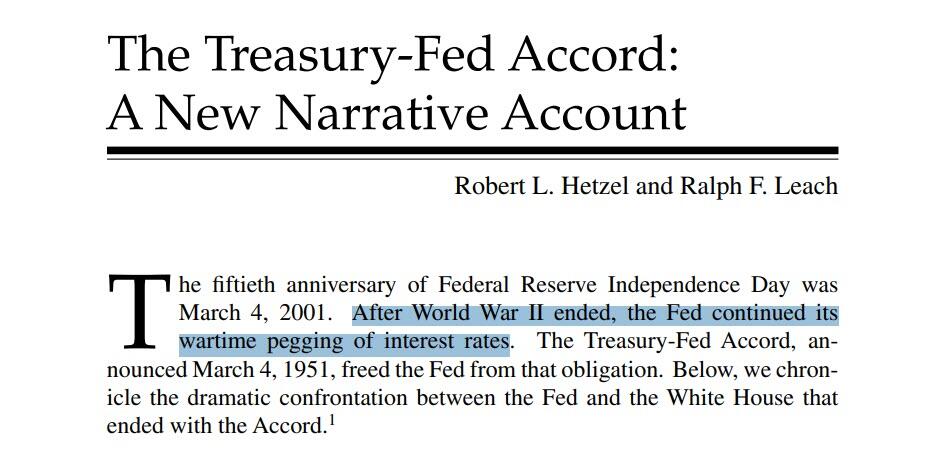

After the war had concluded, there was a heated public disagreement where the Fed sought to raise rates due to inflation, while the Treasury of course preferred the status quo. Siding with the Treasury, President Truman insisted the Fed maintain low interest rates, citing the impact rising interest expenditures had on the deficit. The Fed obliged and continued to cap yields until the 1951 Treasury-Fed Accord settled the disagreement, giving them total authority over setting interest rates that it still holds today.

A rethink of the Treasury-Fed Accord is not unlikely since interest rate policy is already (albeit unofficially) becoming fiscal policy. This is the reality of fiscal dominance - where the Fed's job has nothing to do with employment or inflation, but simply to enable the Treasury and keep its borrowing costs manageable.

US interest expense doubled under Biden from $534BN per year in Q1 2021 to $1124BN per year in Q4 2024 pic.twitter.com/d7tXINXAla

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) April 10, 2025

The interest expense on the debt will grow in the coming year, and keep growing, due to both a rising stock of debt and higher interest rates (higher than when much of the debt was issued). These are forces that DOGE and some real fiscal responsibility can put a dent into, but in reality are an unstoppable train. As this continues, the impact of interest expense will begin to affect other areas of fiscal spending, like entitlements. Income security in the US is a political issue that would supersede concerns over inflation.

By anchoring nominal yields in the face of elevated inflation, the Fed could resolve the interest expense burden, but at the cost of implicitly tolerating deeply negative real interest rates. This is the core mechanism of financial repression: a policy framework where real returns on safe assets are structurally suppressed, capital is directed toward public financing needs, and the real (inflation-adjusted) burden of public debt is quietly reduced over time.

Bottomless Balance Sheets

If foreign capital flows are necessarily replaced with flows from domestic capital, that means domestic balance sheets will be forced to hoard more domestic assets (because foreign balance sheets will not). These domestic balance sheets would thus necessarily expand, pushing the current legal boundaries.

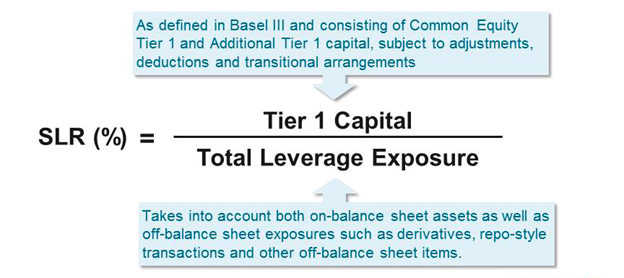

The size (and composition, among other things) of domestic banks are currently limited by a sea of niche, pedantic and frankly pretty boring regulations, including but not limited to leverage ratios, capital ratios, intraday liquidity requirements, and an alphabet soup of others (too many to even begin listing).

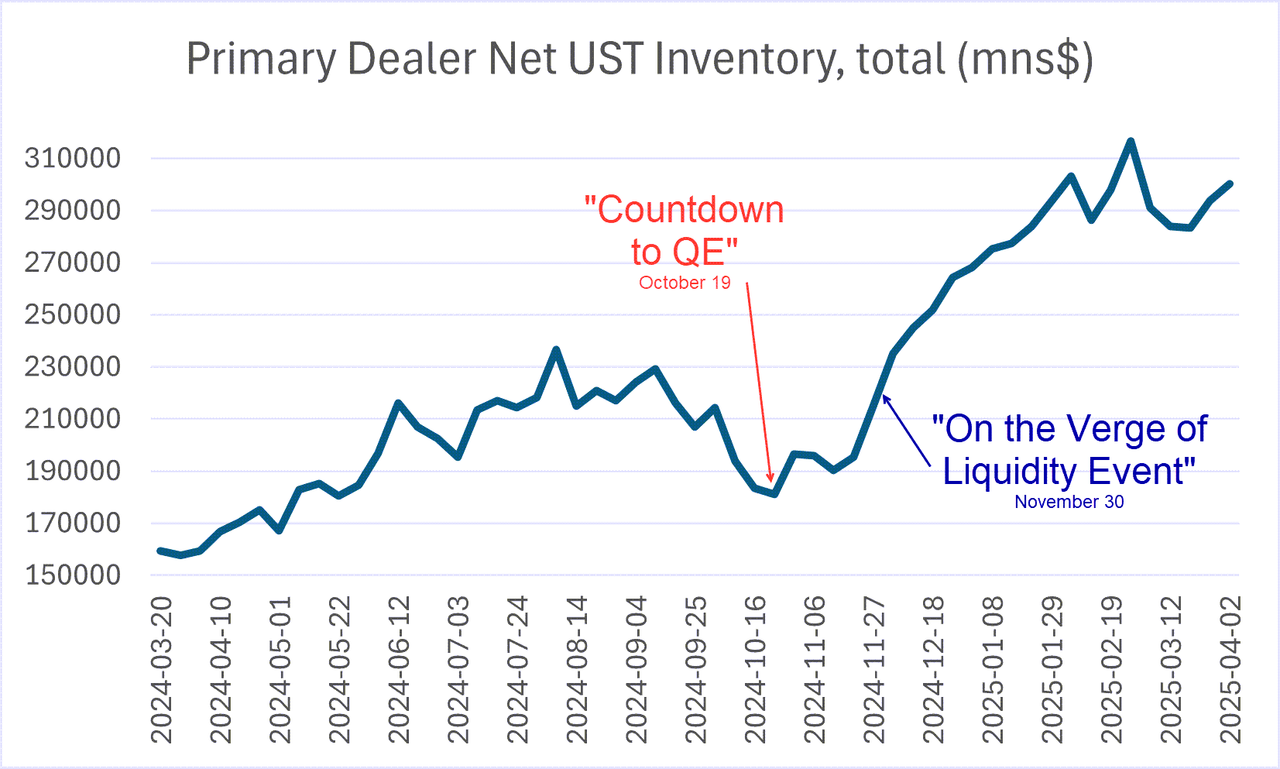

War Finance would call for this regulatory burden to be lifted: banks would have bottomless balance sheets ("war time balance sheets") for assets that support domestic capital: reserves and Treasuries. This is something I said last year was inevitable as the dealers for domestic banks were left to warehouse and finance a massive inventory of Treasuries.

Lo and behold, just days ago, Fed Governor Bowman indicated that she would prioritize exempting Treasuries from the SLR, giving dealers bottomless balance sheets, which back in October I said was probably the only solution and, as I've stressed repeatedly, is mechanically identical to QE.

Bowman has been talking about this change for over a year so we'll see.

— Mike (@DeathTaxesandQE) April 10, 2025

I think dealers need to run into a bind before they go for it. Cash drain from taxes over next couple weeks will do that.

Can't emphasize how huge this is. QE by another name.https://t.co/aZcIsIX1M2

This isn't the Fed talking down yields, the Treasury changing the composition of its issuance to depress them, or one of the other things we might instinctively call "not-QE". This is totally different, truly the closest thing there is to QE without involving the Fed, and opens the door to an endgame where the role of private sector banks fuses with the role of public sector institutions.

What I call bank QE is not something officials can do so easily or without pain. What if they do this and, after a few days, yields keep rising and equities keep falling? They would be out of firepower. Thus, like an investor bottom-picking a collapsing stock, it's my belief that they have to wait for something to break before stepping in.

The fireworks is thus not over and, if my own theory from October holds up, it hasn't even begun.

Foaming the Runway

Like with any crisis, there comes a point where popular support whips up carte blanche for monetary authorities because, if there's one thing Americans don't like, it's feeling unsafe and uncertain. In 2020, the media manufactured hysteria about a virus, and thus popular support for the Fed & the Treasury to do just about anything, including merge together, a plan that was almost perfectly outlined by BlackRock months earlier in August 2019:

Unprecedented policies will be needed to respond to the next economic downturn. Monetary policy is almost exhausted as global interest rates plunge towards zero or below. Fiscal policy on its own will struggle to provide major stimulus in a timely fashion given high debt levels and the typical lags with implementation. Without a clear framework in place, policymakers will inevitably find themselves blurring the boundaries between fiscal and monetary policies.

The BlackRock authors stressed that, at the time, both policy channels would not work unless in perfect sync:

An unprecedented response is needed when monetary policy is exhausted and fiscal policy alone is not enough. That response will likely involve “going direct”: Going direct means the central bank finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders. Going direct, which can be organised in a variety of different ways, works by: 1) bypassing the interest rate channel when this traditional central bank toolkit is exhausted, and; 2) enforcing policy coordination so that the fiscal expansion does not lead to an offsetting increase in interest rates.

The BlackRock plan is an outline for War Finance, which we of course saw unfold during the ensuing Covid downturn. But more recently, like they said in 2019, BlackRock notes that the Fed's "monetary policy space" (room for rate cuts) remains low due to inflation uncertainty. The Treasury's "fiscal space" (room for deficits) is also exhausted, not only because we're already running gargantuan deficits, but because foreign capital is not going to pick up the tab.

War Finance would say the Covid playbook - wherein the Fed and the Treasury coordinate to get central bank money (reserves) directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders - is thus the only way to deal with not only the Covid downturn but the next. Monetary policy must be coupled with the fiscal side. That means monetizing issuance - the Fed will, literally, be money printing.

In this regime, the Fed buys corporate bonds with freshly-printed reserves to extend credit to private industry (that fund business expenses like salaries), no differently than how they buy Treasury bonds with freshly-printed reserves to lend to the US Treasury.

The question is what's this grand event that could compel this? It won't all come at once, but some upcoming stress in bond markets are certainly going to "foam the runway", changing policy and setting precedent that might look like a really simple policy tweak but in reality carries seismic implications downstream.

Through the latter two weeks in April, we will see an unusually large drawdown of bank cash due to April tax receipts, something I first wrote about in October (and in greater depth in November). I arbitrarily estimated it would be around $700 billion, but, being no expert on Treasury inflows and outflows, I was glad to see John Comiskey, who is an expert, arrive at an almost identical number: $692 billion.

I do, projecting tax flows is a component of my model that projects all Treasury flows for each day. I released my daily projections for the 4 big tax receipt categories through May 1 in my latest article.https://t.co/DKGvBrLlc5

— John Comiskey (@Johncomiskey77) March 25, 2025

Since I predicted that exact series of events last year would unfold in April, a lot has evolved, and it's setting up as perfectly as possible - far better than I imagined it would at the time. Even Jamie Dimon seems to be on the same page. Not only did foreign buyers fail to swoop and buy Treasuries from dealers when it made sense to buy (i.e., when the yield curve steepened), as Pozsar would've expected, but the basis trade happened to turn unprofitable at the same time!

That's, as of Thursday, $120 billion more collateral ($30 billion of which are bonds - the most difficult to warehouse) burdening dealers. This is already reflecting in higher balance sheet costs (dealers charge a higher premium to use their balance sheet) as measured by tightening in SOFR swap spreads:

3Y SOFR in Free Fall, plummeting to all time low as funding squeeze emerges. Presumably the @federalreserve is on top of this pic.twitter.com/OCKURkUzkg

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) April 8, 2025

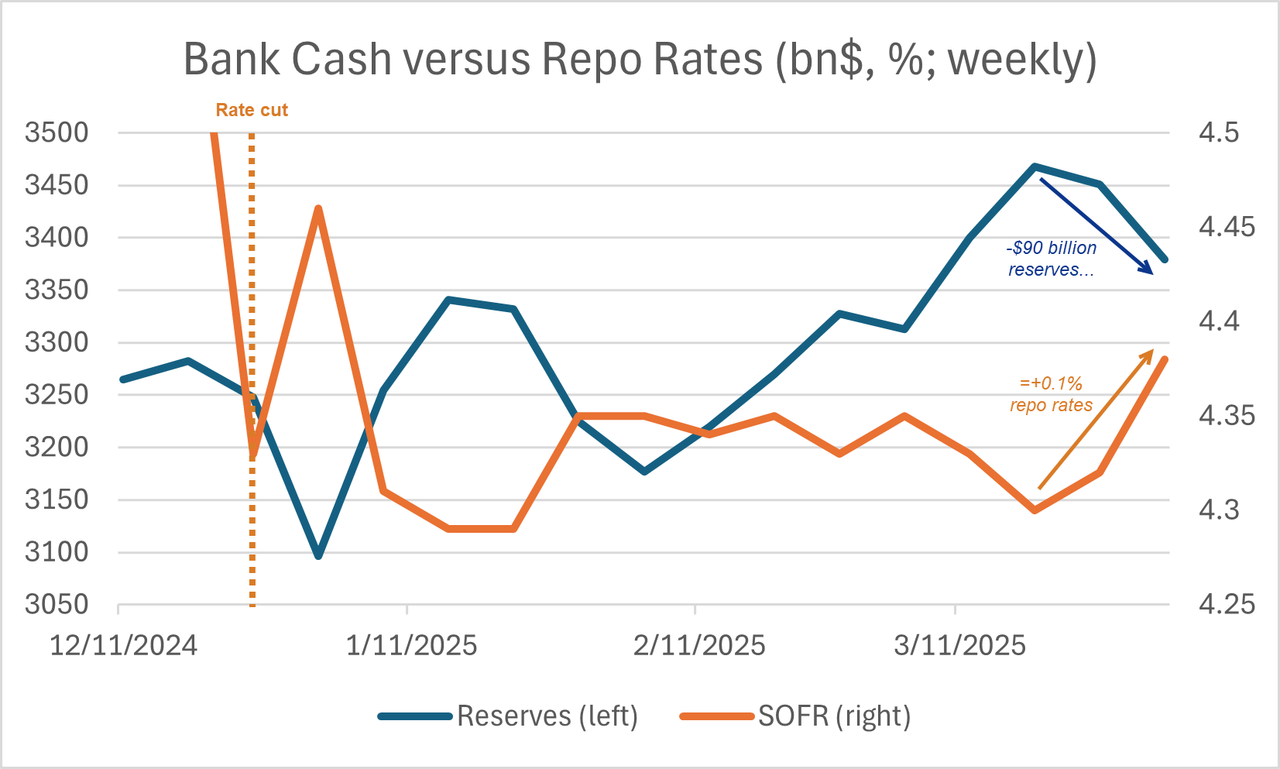

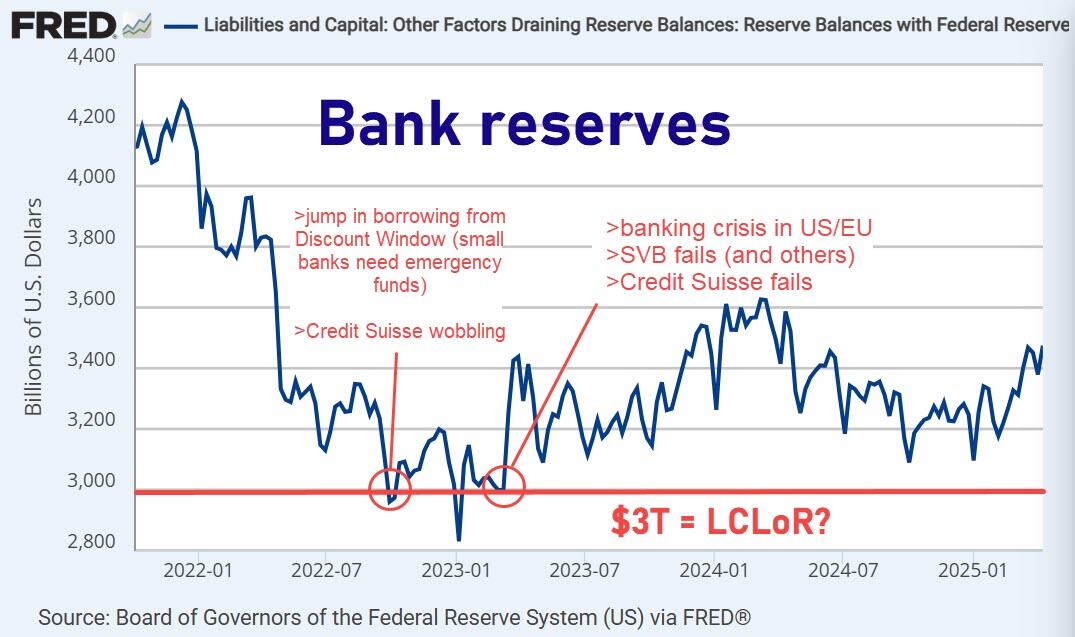

The big question is why hasn't this shown up in repo pressures already? Well, as of this writing it definitely has, but the reason it took until now is because of the debt ceiling:

Treasury has burned through $560BN of its cash balance in the past month. Just $280BN left https://t.co/rGakG2Vqpt pic.twitter.com/8FXCjQg0RY

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 29, 2025

When the Treasury hits its debt ceiling, it begins drawing down on cash held at the Treasury account, which then goes back into the banking system. This has been happening so aggressively that it's supported bank dealers' ability to intermediate all those new Treasuries. I anticipated the debt ceiling would have this effect, but had no idea just how much: every week, the Treasury's account is run down $100 billion, and thus about the same number in reserves reenters the banking system. This has kept a lid on pressures but, at even a mild turn down in reserves, they resurface.

If we just assume John Comiskey is correct and that April tax revenue will be about $700 billion, the drawdown in bank reserves would total about $650 billion over two weeks. Not only will this completely bind dealers' ability to intermediate in collateral markets like Treasury repo (basis trades), but it will also bring us right below $3 trillion - the minimum level of bank cash before stresses appear - a red line which the Fed is clearly watching.

Nonetheless, it would be surprising for something as simple and well-telegraphed as tax season to actually make the entire financial system tremble.

But that's what happened during the September 2019 repo spike, when quarterly taxes withdrew enough reserves from repo lenders such that borrowers were left scrambling to arrange financing. The Fed first ended QT and conducted extensive repo operations, but by October 2019 announced they would inject reserves by purchasing short-term Treasury bills. Within a few months, they shifted to injecting reserves by purchasing longer-term Treasury bonds, along with a host of other things, in QE4.

I'm skeptical to think we'll see the exact same playbook in 2025, and officials still have options, but those are the facts. After some pain later this month or early next month, which could mean anything from a tepid bond selloff to a violent and complete unraveling of the basis trade, officials would hopefully recognize these new challenges faced by the Treasury market...

... and recognize them as more-or-less permanent.

As said in October, I still think it will end with exemption of Treasuries and reserves from the SLR, and probably relief on some other liquidity regulations like risk-weighted capital ratios. Every Treasury dealer I've had a conversation with on this has called SLR exemption for Treasuries a "no brainer", and Fed governor Michelle Bowman has signaled that this change specifically is her priority. That was the Covid playbook, but, this time, the regulations will not be reinstated.

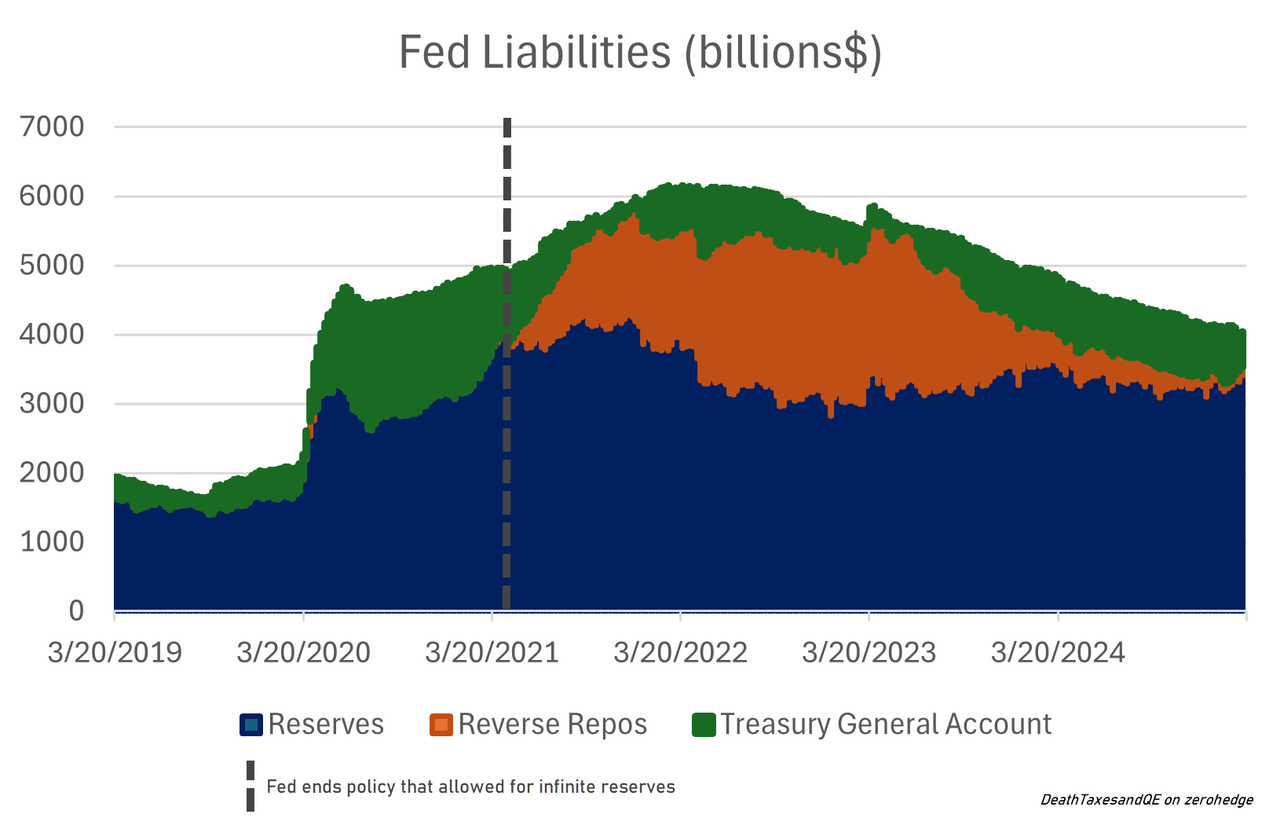

Exempting reserves from the SLR, however, is another huge step - it's the only reason why QE started to bind in 2021. Banks were forced to take all those excess reserves they received from QE trades and shift them into reverse repos with the Fed to comply with regulations. With the exemption, having "too many" reserves becomes an oxymoron.

Exempting reserves from leverage ratios will foam the runway for future YCC, which I'm pretty confident will be chaired by Michelle Bowman who replaces Powell when his term ends in May 2026.

Needless to say, when the rule change does come into effect, that will be the bottom - certainly in bonds but also in equities - for the near future. All these big policy changes won't all come crashing in at once, at least I don't think they will.

But, as the saying goes, "The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry."