The Sun’s Secret Symphony of Chaos

Cycles are the natural rhythms that govern everything from the cosmos to economies. In finance, the business cycle—comprising periods of expansion, peak, contraction, and trough—shapes everything from interest rates to employment. Driven by human behaviour, credit dynamics, and policy responses, it reflects the collective boom-bust psychology. But behind this economic heartbeat lies a deeper, often overlooked rhythm: the solar cycle.

The solar cycle is the Sun’s version of a mood swing—flipping between quiet and wild about every 11 years. It’s all thanks to its ever-twisting magnetic field, which gives us everything from calm sunny days to explosive tantrums like solar flares and coronal mass ejections (a.k.a. giant plasma burps).

The Sun’s activity can be tracked by counting sunspots—those dark patches on its surface caused by magnetic mayhem that cool things down just enough to look like acne. When the Sun's covered in them, it's called solar maximum; when it’s nearly spotless, we call it solar minimum (and maybe suggest it take a nap).

Since 1755, numbering of these cycles like have been recorded as solar seasons. Right now, we’re in cycle 25, which kicked off in December 2019. It hit its dramatic peak around October 2024 and is now settling down again by 2030. So far, cycle 25 has been fierier than forecasted, but still not quite as wild as the Sun’s greatest hits from the 20th century.

Solar Cycle 25 showed up to the party with more energy than expected—but it’s still not quite the rockstar some of its 20th-century ancestors were. Early forecasts, courtesy of a tag team from NOAA, NASA, and the International Space Environmental Services (yes, that’s a thing), predicted it would be a repeat of the last snoozefest, Cycle 24—the weakest in nearly a century.

Back in 2019, the official Solar Cycle Prediction Panel confidently called for a peak sunspot number of 115 (using the 13-month smoothed average) around July 2025. That’s nearly identical to Cycle 24’s yawn-worthy peak of 116.4 in April 2014. So far, Cycle 25 has outpaced those expectations—but it’s still far from breaking records. Think: surprising underdog, not solar heavyweight champ.

In the 19th century, British economist William Stanley Jevons took one look at sunspots and decided they were behind the ups and downs of the economy. Not bankers, the Sun. He noticed that “commercial crises” (what we now call recessions) seemed to happen every 10–11 years, just like the solar cycle. Jevons called it a “beautiful coincidence,” which, of course, is how all serious science begins. Naturally, the reason is that solar flares are wrecking harvests, which in turn crashed markets. Econometrics, meet astrology.

But Jevons was a minimalist compared to Russian scientist Alexander Chizhevsky, who looked at the Sun and saw the entire arc of human history. He claimed that revolutions, wars, and general mayhem peaked right around solar maximums. He even charted centuries of upheaval—from 500 B.C. to 1922—against sunspot records, finding a suspicious number of uprisings when the Sun was feeling particularly blotchy. Chizhevsky split the solar cycle into four phases, starting with sleepy authoritarianism, followed by political organizing, then full-blown revolutions, and finally burnout and apathy. Basically, humanity on an 11-year caffeine binge.

In a nutshell, the Sun has been moonlighting as an economic hitman.

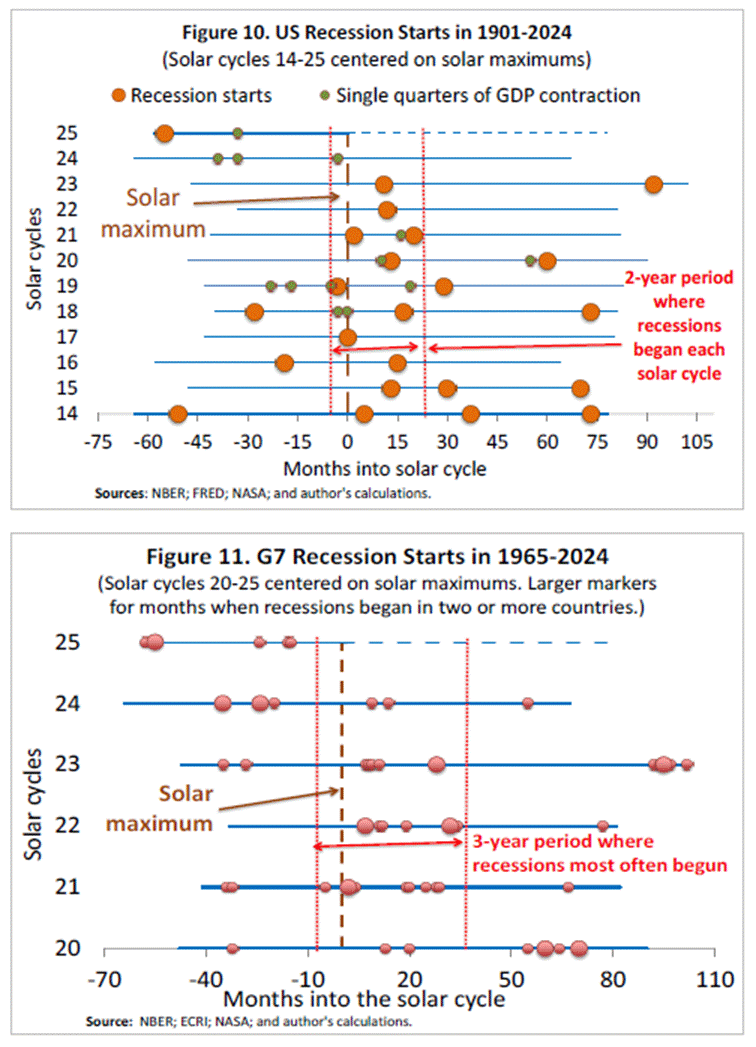

From 1901 to 2008, every time sunspots peaked, the U.S. economy got the cosmic flu. Out of ten solar cycles (cycles 14–23), eleven recessions broke out within a cozy two-year window surrounding the solar maximum—either just before or not long after. Statistically, the odds of this being pure coincidence are less than 0.1%. That’s right: the same probability as a Fed chair admitting they’re just winging it. But wait—it gets weirder. Since 1933, the relationship gets even tighter: 8 out of 13 post-Depression recessions hit during this same solar sweet spot. Before that? The 19th century was a bit more... freestyle. Recessions popped up all over the cycle, with no regard for solar etiquette.

Why the shift after the 1930s? Blame it on the Great Depression. That cataclysm scared policymakers straight. Recessions became shorter, less frequent, probably thanks to government intervention (read: stimulus cocktails). Random shocks like bank runs stopped triggering full-blown economic meltdowns—unless the Sun demanded it. And it’s not just about recession starts. Between 1933 and 2008, the economy spent a third of its time in a downturn within the three years after a solar maximum. At the peak of this trend—about 18 months after sunspot highs—recessions were more common than not. The correlation between solar activity and economic misery even reached 0.21 (which is high for this sort of celestial fortune-telling). Of course, once you extend the analysis to include the more chaotic 19th century, all the solar-economy love disappears. Turns out, sunspot cycles only got their economic act together once the U.S. did. Coincidence? Maybe. But if Wall Street ever starts trading solar flares, you’ll know why.

Nobody knows exactly why, but it turns out the Sun might have a side gig as a recession DJ—dropping economic downturns every time it hits peak activity. For over a century, nearly every solar maximum synced suspiciously well with a U.S. recession. That cosmic streak held strong until 2014, when the Sun's weak solar cycle 24 peaked... and the U.S. economy yawned and kept going. Past research suggests the U.S. is most recession-prone within a two-year window around these solar highs. The rest of the G7 is just as sun-sensitive—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the UK have also shown a knack for stumbling into recessions within three years of solar peaks. Even worse, when their recessions overlap, it can trigger a full-on global slowdown.

Once we accept that recessions tend to cluster around solar maximums, it’s logical to expect that other business cycle indicators would also show signs of strain during those periods. And that’s exactly what the data says.

Take the OECD’s Composite Leading Indicators (CLIs), built specifically to anticipate economic turning points. For the U.S., during solar cycles 19 through 23 (1955–2008), the CLI consistently dropped in the three years surrounding solar peaks—bottoming out roughly 2.5 years after. Statistically, the CLI had a notable negative correlation (-0.15) with sunspot activity, lagging by 24 months. This wasn’t just a U.S. quirk—similar patterns were found across all G7 countries (except Japan), and even across broader OECD and BRICS-type economies.

The trend continues with the Aruoba-Diebold-Scotti (ADS) business conditions index, which blends various high- and low-frequency U.S. data. From 1964 to 2008, the ADS index showed clearly weaker-than-average conditions in the three years following solar maximums, with a statistically significant negative correlation to sunspot activity. Even more striking is the unemployment data. From 1948 to 2014, every U.S. solar maximum lined up closely with a low in the unemployment rate—followed by a sharp upward turn peaking 2–3 years later. In short, sunspot highs seem to precede job market lows. Canada mirrored the U.S., while Japan’s historically stable unemployment rate showed less connection—likely due to its unique labor market dynamics. European G7 countries showed a weaker relationship, partly due to inconsistent long-term data. As you'd expect, GDP growth also lags behind the Sun. U.S. GDP growth rates weakened consistently in the three years after solar peaks between 1954 and 2008. The same pattern shows up in aggregated G7 GDP, broader advanced economies, and even global GDP growth.

In sum: the Sun may not be managing your portfolio, but it does seem to cast a shadow over global business cycles—often dimming growth, employment, and confidence in the years after it reaches its fiery peak.

Anyone with a functioning brainstem and Econ 101 under their belt knows that thriving economies run on cheap and abundant supply of energy and food. Unfortunately, the climate change crowd—especially in Europe and California—missed the memo. They're busy banning cows and gas stoves while Mother Nature is quietly prepping for her next plot twist: a Solar Minimum.

As of July 2025, the planet earth is in Solar Cycle 25—the sun’s version of a Netflix-and-chill phase. It kicked off in December 2019 and might run till 2030, with forecasts ranging from “meh” to “Maunder Minimum” (a.k.a. Little Ice Age 2.0). When the sun gets quiet, weird things happen—like massive volcanic eruptions, planetary cooling, crop failures, and people discovering what rationing tastes like.

Here's the kicker: over the past 8,000 years, there’s been a strong inverse relationship between sunspot activity and major volcanic eruptions (R = -0.72, for the stats nerds). Fewer sunspots? Boom—more magma. It's not magic; it's magnetized solar wind mucking about with Earth’s geology. And yes, the green zealots will figure this out thanks to tree rings and radioactive carbon (science!). The last 2,500 years have seen a drop in sunspot averages—and surprise!—volcanic mayhem picked up. Some data even suggest a tipping point: if sunspot averages dip below 17, the Earth gets a fireworks show from beneath. Just one giant eruption could choke the skies, crash crops, and make the next supply chain crisis look like a picnic. As solar activity declines (blue line), volcanic activity (red line) appears to rise—adding some historical weight to the idea that fewer sunspots might mean more eruptions, more cooling, and possibly more chaos.

While the 47th US president has been keen to ditch the climate Kool-Aid and embrace energy independence, reality might hit harder than any policy shift. If the sun keeps dozing off, the real "climate emergency" may involve parkas, panic buying, and food riots—not rising seas. So forget carbon credits. You might want to invest in greenhouses, wool socks, and maybe a few cans of beans.

Research indicates a correlation between the solar cycle—particularly periods of low solar activity known as solar minimum—and increased volcanic activity. During solar minima, reduced sunspot activity allows for greater penetration of cosmic rays into the Earth's atmosphere, which may influence cloud nucleation, atmospheric pressure patterns, and ultimately seismic activity. Some studies suggest that decreased solar irradiance can affect the Earth's magnetosphere and stratospheric temperatures, potentially contributing to tectonic instability. Historical data reveal that major volcanic eruptions, such as the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora during the Dalton Minimum, often coincide with prolonged solar minima, implying a possible link between reduced solar activity and heightened volcanism. Although causality remains a subject of ongoing research, the relationship between solar variability and volcanic activity is increasingly recognized as a significant factor in long-term climate variability. Volcanic eruptions inject substantial amounts of aerosols and gases into the stratosphere, which can reduce solar irradiance reaching the Earth's surface and result in measurable surface cooling lasting one to three years.

Back in 1815, Mount Tambora decided to throw the biggest volcanic tantrum in recorded history—blasting out enough rock and ash to cover the atmosphere and silence nearby villages for good. With a VEI of 7, it was loud enough to be heard hundreds of miles away and deadly enough to wipe out at least 10,000 islanders and 35,000 homes.

https://www.dw.com/en/the-historic-tambora-eruption-a-devastating-volcanic-event/video-69529475

The fallout? The infamous “Year Without a Summer” in 1816, when global temps took a nosedive, crops failed, and famine spread like wildfire. Oh, and it also kickstarted the first global cholera pandemic and an economic slump in the U.S.—talk about aftershocks.

Scientists think this volcanic drama was linked to the Dalton Minimum, a solar chill-out period that boosted cosmic rays, possibly nudging volcanoes into action. Others say solar flares might even mess with Earth’s spin, triggering mini earthquakes that can either unleash or delay volcanic blowups. Either way, Mother Nature showed she has a flair for dramatic sequels.

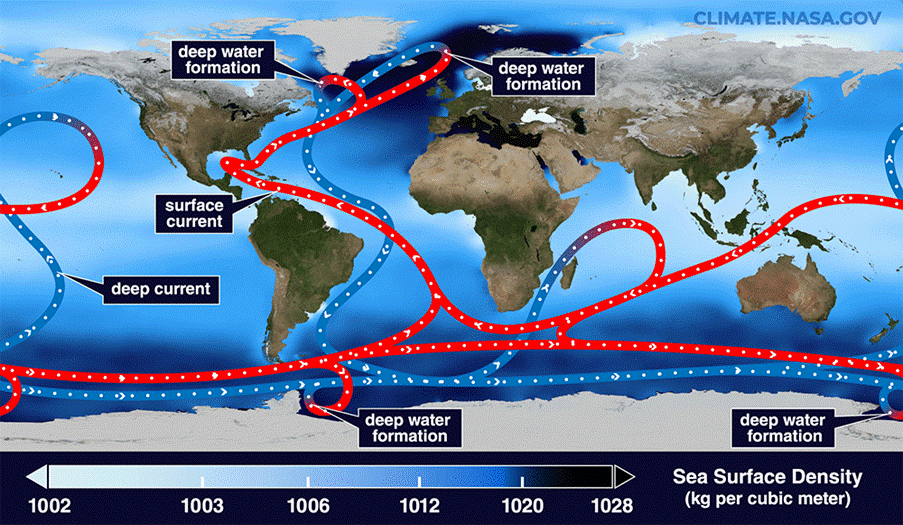

By now everyone’s should know that the solar cycle and volcanic eruptions mess with Earth’s climate. During a solar minimum, when the sun decides to take a little nap, things get chillier up here. Add to that a massive volcanic tantrum like Mount Tambora’s in 1815, which spewed enough ash and sulfur dioxide to put a giant shade over the planet, and voilà—you get the delightful “Volcanic Winter” of 1816, or as it’s lovingly called, the “Year Without a Summer.” The solar minimum also loves to throw a wrench into the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation—the fancy name for the Gulf Stream’s slow-mo performance—meaning less warm water heading to Europe and North America, making things even chillier. So, when solar slumps, volcanoes blow, and ocean currents dawdle, we get a cocktail of climatic chaos that’s as subtle as a sledgehammer.

Some crops didn’t even wait for the volcanic winter to start throwing a tantrum. While the world is still busy arguing if climate change means sweating buckets, Japan is already living the future—welcome to the Rice Apocalypse. Who needs a volcanic winter or a solar minimum when you can just pay double for your daily bowl of rice? What was a humble ¥2,168 for 5 kg back in January 2024 has blossomed into a fancy ¥4,200 by spring 2025. That’s right, rice has officially earned its spot in the luxury goods hall of fame. Bon appétit, served with a generous side of inflation!

Japan’s rice shelves are so bare the government’s had to heroically raid its “emergency stash” for the third time in 3 months, dropping another 200,000 metric tons into the wild. That’s on top of the 600,000+ tons already unleashed since March—because who doesn’t love a good rationing drama? Minister Koizumi assures us they’re “responding without slowing down,” which apparently means keeping the economy stable by handing out 3-year-old rice and blaming it for wage stagnation. Meanwhile, the ruling LDP, in power since 1955, faces a July Upper House election with all the charm of soggy sushi. To add insult to injury, the next rice harvest isn’t until August—and it’s shaping up to be a historic disaster, with the smallest planted area since 1900. Farmers, understandably fed up, are protesting a government that pays billions to not grow food instead of subsidizing actual harvests. Now the Ministry of Agriculture is begging them to go back to rice farming, but convincing a younger generation stuck with low pay and heavy regulation? Good luck with that. And just when you think things couldn’t get messier—Japan’s flirting with a sovereign debt crisis. But for now, it’s the empty rice bowls reminding everyone that the real shortage is in competent leadership.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/21/japan-farm-minister-resigns-rice-price

Outside of politics, no need of a PhD in finance to figure out that rising food and agricultural commodity prices push inflation up the ladder. So it’s no shocker that the Bloomberg Agriculture Commodity Index climbing is one of the many sparks that pushed the Gold to US Treasury Ratio above its 7-year moving average—the rare indicator that’s refreshingly free from any propaganda spin, quietly signaling that, yes, the US economy is very much swimming in an inflationary sea.

Gold to US Treasury Ratio (blue line); 7-Year Moving Average of Gold to US Treasury Ratio (red line); Bloomberg Agriculture Commodity Index (green line).

As anyone with even a pinch of common sense knows, scarcity pushes food prices up, and when food gets more expensive, consumers end up paying more for less on their plates. So it shouldn’t surprise anyone that a rise in the Bloomberg Agriculture Commodity Index has also been, among other things, a leading indicator for the S&P 500 to Oil ratio — the only truly unbiased gauge telling us whether the US economy is cruising in a boom or heading for a bust, depending on where it sits relative to its 7-year moving average.

S&P 500 Index to Oil Ratio (blue line); 7-Year Moving Average of S&P 500 Index to Oil (red line); Bloomberg Agriculture Commodity Index (axis inverted; green line).

As the solar minimum ushers in yet another volcanic winter which will bring economic crisis but also wars, chaos and regime changes, investors would do well to remember that since the Manipulator in Chief took office, the S&P 500-to-gold ratio has stubbornly stayed below its 7-year moving average—a subtle but serious alarm for anyone actually paying attention to cycles. With the war cycle turning up the heat, it’s time to stop pretending we can bend the business cycle to our will. Instead, savvy investors need to adapt—shifting their mindset from chasing Return ON Capital to prioritizing Return OF Capital.

Read more and discover how to trade it here: https://themacrobutler.substack.com/p/the-suns-secret-symphony-of-chaos

If this research has inspired you to invest in gold and silver, consider GoldSilver.com to buy your physical gold:

https://goldsilver.com/?aff=TMB

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.