From Store of Value to Paper Claim: Why Currency Isn’t Money?

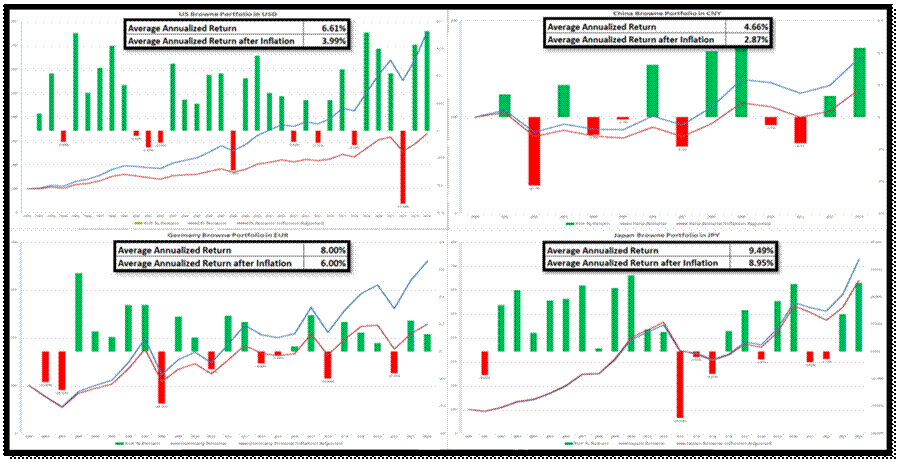

Anyone with even a minimum level of financial literacy (the kind you get after surviving one dinner conversation with your accountant uncle) should know that Harry Browne’s good old-fashioned Permanent Portfolio is the financial equivalent of comfort food — it works anywhere: the US, Europe, Japan, even China. It quietly delivers steady, inflation-adjusted returns with minimal drama or drawdowns. In other words, it’s the portfolio version of a monk — calm, balanced, and always unbothered by market tantrums.

The main reason is that the Permanent portfolio is made of four simple ingredients, equally weighted: Cash, Bonds, Equities, and Gold, which mixed together on an equal weigjht are able to deliver a relatively smooth sailing accrros the four season of the business cycle.

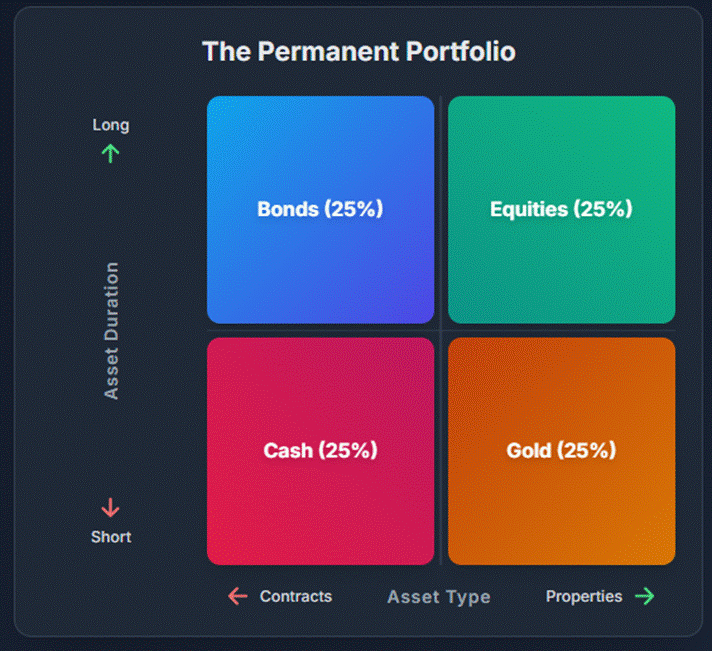

Within the Permanent Portfolio, financial assets fall into two main camps: contracts—legally binding promises of future payments, like bonds and cash —and properties, which represent ownership claims, through stocks and gold. Some of these assets have long maturities, such as government bonds and equities, while others are short-term, like cash and gold. In essence, this “forever portfolio” can be visualized as four quadrants formed by two axes: properties versus contracts, and long versus short duration—a simple yet elegant framework for balancing risk, reward, and resilience across time.

While investors love to write epic sagas about stocks, bonds, and gold, cash rarely gets more than a footnote—like the quiet kid who always does his homework. Yet in Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio, cash is the unsung hero: the stabilizer, the shock absorber, and the stash of “dry powder” ready to strike when panic hits. It doesn’t aim for glory or big returns—just calm reliability. Think of it as the portfolio’s zen master: patient, liquid, and always ready to buy bargains when everyone else loses their cool.

A common mistake among investors is mixing up cash, money, and currency—as if they were triplets when in fact, they barely speak to each other.

Money is the timeless social invention that keeps civilization from collapsing back into barter chaos. It plays three roles: it lets us trade stuff, measure stuff, and (hopefully) keep the value of our stuff over time—though inflation loves to crash that last party. Money is essentially proof of work—the crystallized sweat of human effort, like gold and silver once were, forged through extraction, labor, and scarcity.

https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/value-money/online/origins-money/forms-money

Currency, on the other hand, is more like proof of faith—it works only because we believe the central bank isn’t having a printing spree. While money endures across centuries, currency tends to age like milk—spoiling fast whenever governments can’t resist the temptation to print their way to prosperity. Currency is money’s loud, flashy cousin—the one that actually goes out into the world, gets passed around, and makes the economy spin. It’s the practical, spendable form of money: banknotes, coins, and now digital balances that governments and central banks bless as legal tender. In short, it’s how we express and trade value every day—though unlike real money, it tends to lose its charm (and purchasing power) the more politicians “manage” it.

Historically, money has gone from shiny stuff you could dig out of the ground to numbers you can’t even see on a screen. Gold and silver once ruled because they were scarce and hard to fake; now we rely on fiat currencies—valuable mostly because governments say so and we collectively nod along. In the digital age, money lives as entries in databases, reminding us that its true worth doesn’t come from metal or paper, but from faith—faith in the issuer, in the system, and in the idea that tomorrow someone else will still believe in it too.

Conceptually, money is what you want when there’s nothing else you want — the ultimate placeholder for value. Currency, on the other hand, is money’s physical (or digital) costume — the medium that lets us actually trade stuff. Back in the day, currencies were backed by gold or silver, giving them real substance. Today, they’re backed by trust — a fragile belief that governments won’t mess things up too badly. Money isn’t just coins—it’s the glue that holds economies and societies together. At its core, it plays three roles: a medium of exchange to simplify trade, a unit of account to measure value, and a store of value to preserve purchasing power. But deeper than that, money is a social contract—its power comes from trust. When that trust erodes, money loses its magic. True money is earned, not printed. Gold and silver historically embodied real labor, effort, and scarcity, giving them lasting value. Fiat currency, by contrast, is conjured from thin air by central banks, severing the link between work and value and opening the door to public distrust which ultimately cement inflation. Money reflects productivity; currency reflects decree.

In short, money is the idea, currency is the performance — a symbol that only works as long as the audience keeps clapping.

Most people think they’re saving money… but they’re really just hoarding currency — and when the curtain falls, that little misunderstanding can wipe out a lifetime of hard-earned value.

The difference between money and currency is like the gap between real food and fast food — one nourishes, the other just keeps you going (for now). Money is the timeless store of value — scarce, durable, and rooted in real effort, like gold. Currency is its flashy sidekick, the stuff we actually use to buy coffee and pay taxes.

Back when currencies were backed by gold or silver, they had some real weight. Today, they’re backed by government promises and collective optimism — a risky combo at best. Money endures through centuries; currency just circulates until it doesn’t. In short, money preserves wealth, currency spends it — and the more of it governments print, the faster it spoils. Currencies come with passports — they have an issuer, a jurisdiction, and an expiration date on your purchasing power. Money, on the other hand, is a free spirit: borderless, timeless, and nobody’s liability. Fiat currencies like the USD or EUR are basically the frequent flyer miles of finance — great for short-term transactions, terrible for long-term savings. They’re designed to move, not to last. And just like airline points, their value tends to vanish right after someone changes the rules.

You save money; you spend currency.

The market itself decides what’s money and what’s just currency—you hoard the first and spend the second. That’s basically Gresham’s Law in action: bad money drives out good. When two types of money circulate, people stash the good stuff (the one with real value) and get rid of the bad (the one politicians keep printing).

Back in the coin-clipping days, folks melted down the solid silver and spent the cheapened coins. Today, the same logic applies—only the tools have changed. Instead of melting coins, people swap paper money for gold, whenever central banks get printing-happy.

In short: gold is great money, fiat is great currency—one you save, the other you spend. And like a good marriage, they coexist because they serve very different purposes.

The money-versus-currency story isn’t new—just ask the Roman denarius. Introduced around 211 BC, it was initially real money: a coin nearly pure silver, valued for its intrinsic worth, not because the state said so. Scarce, tangible, and tied to effort, it anchored purchasing power. But as Rome expanded and expenses ballooned—wars, public works, and handouts—emperors started shaving silver from the denarius to stretch the treasury. By the 3rd century AD, under rulers like Caracalla and Diocletian, the denarius had lost almost all its silver. What remained was currency: a state-issued medium of exchange backed by authority, not metal. Trust eroded, prices soared, and the economy faltered—a classic case of money turning into currency, proving that convenience alone can’t replace real value.

The U.S. has been grappling with the money-versus-currency divide for centuries. Colonial settlers relied on commodity money—Spanish silver dollars, gold coins, even tobacco—that held real value. Enter the Revolutionary War, and the Continental Congress printed fiat notes with no backing, giving rise to the immortal line: “not worth a Continental.” The Constitution later anchored currency to gold and silver, but history kept testing the limits—Civil War greenbacks proved the government could issue unbacked currency when needed. The Federal Reserve, established in 1913, gradually cemented fiat practices, and Nixon’s 1971 end of Bretton Woods severed the dollar from gold entirely. By 2025, the split is clear: the dollar dominates as medium of exchange, and unit of account—but its real purchasing power depends entirely on policy, and global confidence. Money represents tangible value; currency represents authority—and in America, the line has been blurred for over two centuries.

When a currency stops being real money—losing its ability to store value, measure worth, or facilitate trade—chaos ensues. Take Weimar Germany in the early 1920s: the Papiermark had become pure paper, untethered from any tangible value. What once bought a loaf of bread cost billions of marks a few years later, sometimes changing hourly. People raced to spend cash immediately, knowing holding it meant guaranteed loss. Savings vanished, wages became meaningless, and barter—or foreign currency—took over daily life. The harsh truth is that without confidence or intrinsic value, currency isn’t money—it’s just colorful paper that wreaks havoc.

Money only works if it’s scarce—too much of it, and it’s like handing out free cookies: suddenly nobody values them. Scarcity gives money its power as a medium of exchange and a unit of account. Cash used to have this magic, but ever since the gold standard faded and central banks started their wizardry with QE and negative rates, currency lost its mojo. Now it’s just “loose money”—easy to spend, impossible to hoard without losing value.

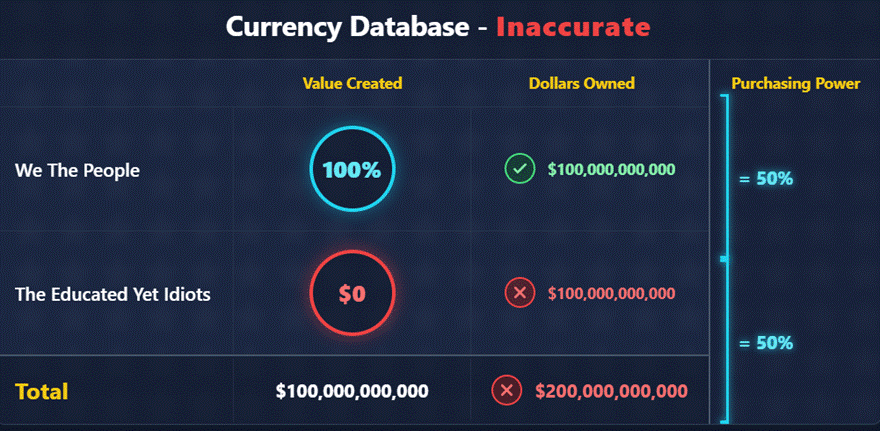

Picture this: the economy has $100 billion of real wealth. The government conjures another $100 billion out of thin air via QE. Boom—nominal money doubles, real assets stay the same. Prices surge, the newly printed cash flows first to insiders, and everyone else—savers and wage earners—gets a hidden inflation tax. In short, cash is no longer real money; it’s a political magic trick that slowly eats your purchasing power. Scarce money built on effort? Good. Endless paper conjured by decree? Not so much.

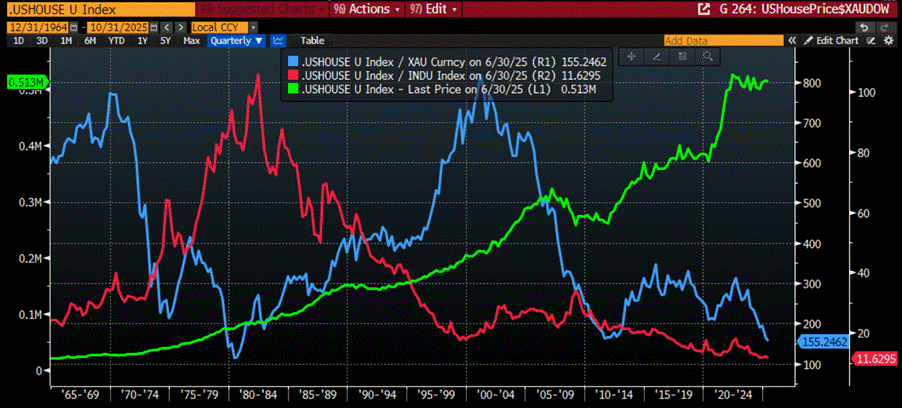

Over the past 60 years, U.S. housing prices tell very different stories depending on the lens you use. In dollar terms, prices have steadily climbed, spiking during credit booms and dipping modestly in recessions. Measured in gold, however, the picture is far more stable: a $23,000 house in the 1964 equaled about 595 ounces of gold, while today’s $530,000 home is roughly 155 ounces—that in gold terms the price of home in the US has declined by more than 70%, far less advantageous than the dollar numbers suggest. Fiat inflation has blown up nominal prices, while gold reveals the intrinsic, long-term value. Look at housing versus the DJIA, and another story emerges. A 1964s home cost about 24 unit of the Dow; today, it’s roughtly 12 unit of Dow Jones.

Price of an average American house in ounce of gold (blue line); in unit of Dow Jones (red line); in nominal USD (green line).

History shows that holding cash when ‘Educated Yet Idiots’ run the show—has often been a fast track to losing wealth. Structural inflation, currency debasement, and chronic economic mismanagement have repeatedly eroded the real value of savings. What looks like security on paper quickly turns into poverty, as rising prices and collapsing purchasing power eat away at wealth. In these structurally inflationary and chaotic economies, cash isn’t just idle—it’s a liability. In a structurally inflationary world, cash is basically a slow-motion wealth destroyer. Its purchasing power leaks away steadily, while real assets—like gold, silver, commodities, and even stocks—actually preserve or grow value. Short-term deposits or money market funds most of the time lag behind inflation, quietly draining savings. History, from Weimar Germany to modern high-inflation episodes, shows that cash isn’t a safe haven—it’s a liability, steadily leaving investors behind in the race against rising prices.

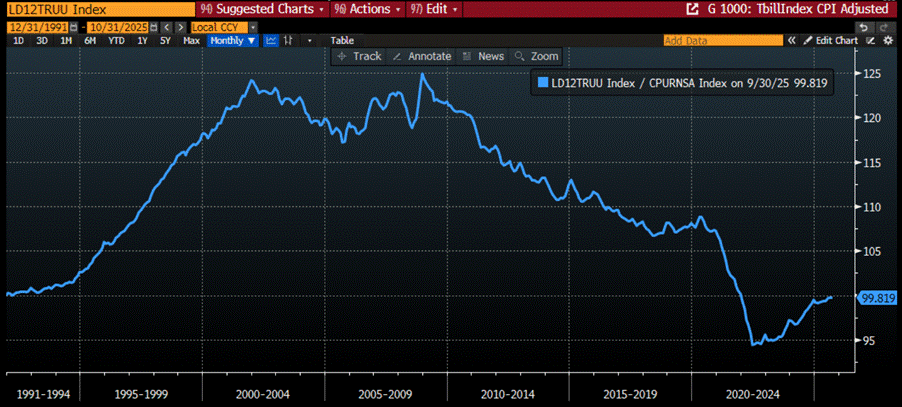

Bloomberg US Treasury Bill 1-3 Months Index in USD terms adjusted to CP-Lie rebased at 100 as December 31st, 1991.

Since the early 2020s, policy choices by what can only be called the “Educated Yet Idiots” have amplified global economic and geopolitical chaos, steadily eroding the real value of cash—even when measured against the official CP-Lie. Inflation, currency debasement, and aggressive monetary interventions have made holding cash far from safe; each year, the same dollar buys less and less, from basic goods to everyday services. In a world where financial illiteracy drives policy and fiscal mismanagement is routine, cash isn’t just stagnant—it’s a losing asset, helplessly watching purchasing power slowly but relentlessly decay.

US Aggregate Chaos Index (blue line); Bloomberg US Treasury Bill 1-3 Months Index in USD terms adjusted to CP-Lie rebased at 100 as December 31st, 1991. (axis inverted ; red line).

Read more and discover how to trade it here: https://themacrobutler.substack.com/p/from-store-of-value-to-paper-claim

Join The Macro Butler on Telegram here : https://t.me/TheMacroButlerSubstack

You can contact The Macro Butler at info@themacrobutler.com

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.