Mercantilism: The New Great Game

The Return of Strategic History

Authored by GoldFix for Scottsdale Mint

The recent revival of Monroe Doctrine comparisons in US foreign policy reflects more than rhetorical nostalgia. While the doctrine historically framed American dominance in the Western Hemisphere, today’s geopolitical posture extends well beyond regional containment. The current environment resembles a broader and more fragmented struggle for global influence.

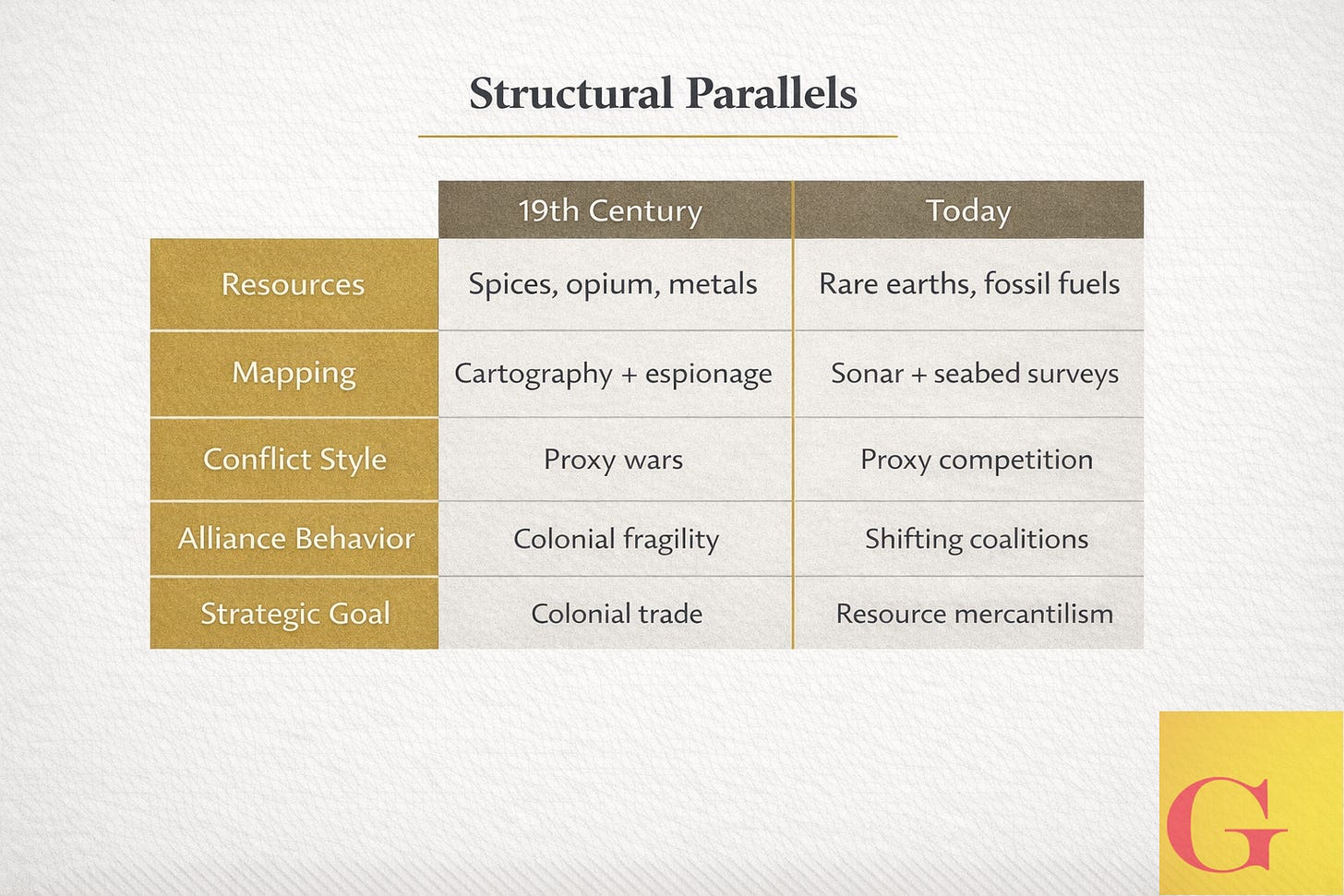

The closer historical parallel is not hemispheric protectionism according to an FT Oped by Rana.Foroohar but the nineteenth-century “Great Game” between Britain and Russia. That conflict unfolded through indirect competition, proxy maneuvering, shifting alliances, and prolonged strategic positioning across Central Asia. The modern version replaces Britain and Russia with the United States and China.

This new great game revolves around three central pillars: mining, mapping, and mercantilism.

Mining: The Resource Contest

In the original great game, control of India and Central Asia mattered for spices, precious metals, and opium. Today, the prize has shifted to fossil fuels, rare earth minerals, and strategic infrastructure.

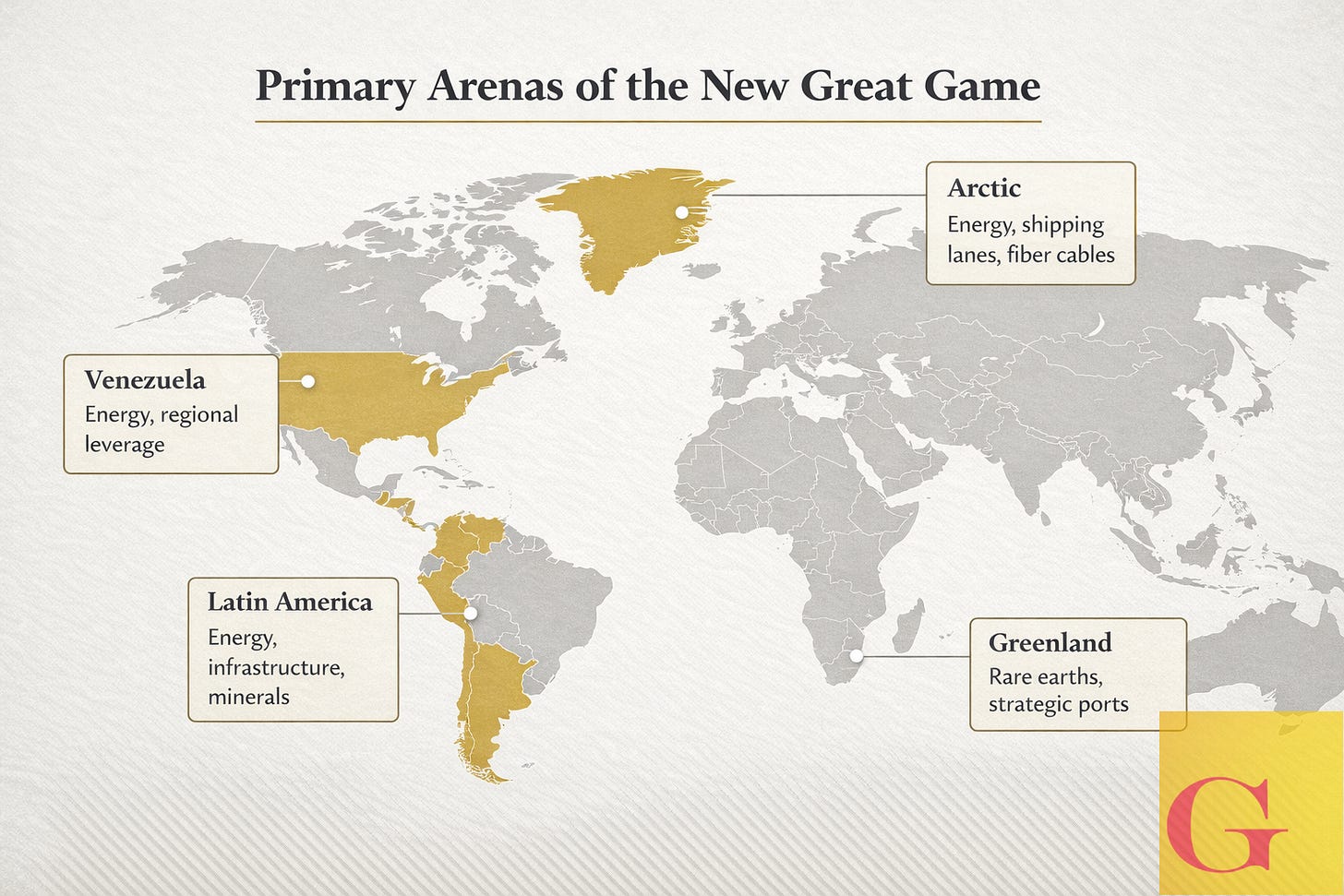

Latin America and the Arctic are now primary theaters.

Venezuela and Greenland occupy particular importance. Both offer mineral wealth, energy resources, and access to strategic ports. Chinese infrastructure investment in Latin America helped motivate recent US action in Venezuela, while Greenland has become a focal point of Arctic competition.

China already maintains a state-owned presence in Greenland’s Kvanefjeld mineral field and has expanded diplomatic engagement there. The Arctic is no longer simply a frozen frontier. It is a zone of energy potential, fisheries, shipping lanes, fiber-optic cable routes, and geopolitical leverage.

For Washington, the objective is not merely access to minerals, but the exclusion of China from Arctic strategic space. Chinese presence in the region often operates through Russian partnerships, complicating Western security planning.

Mapping: Geography as Strategy

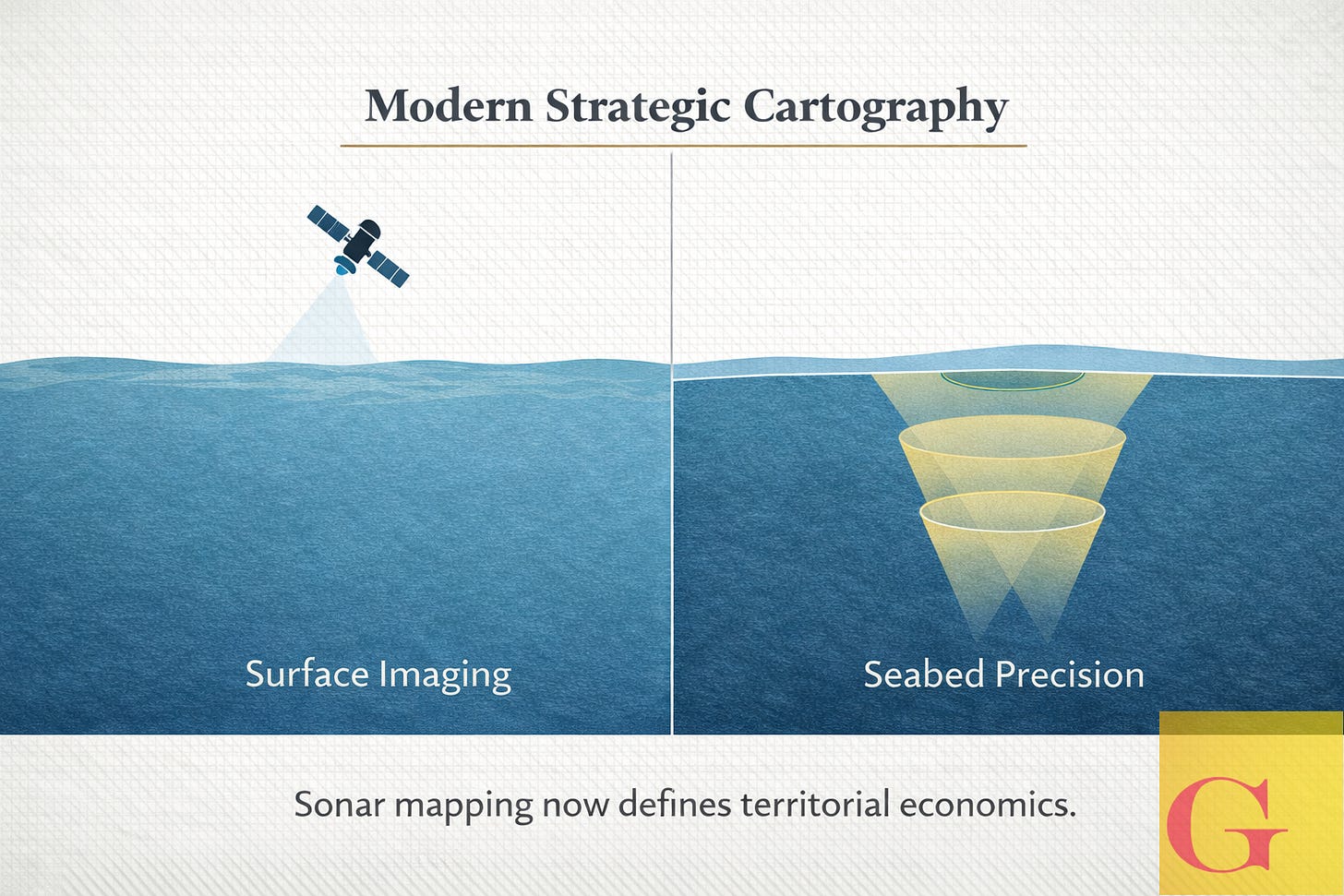

Resource competition requires precise geographic knowledge. Both the United States and China are investing heavily in seabed mapping, increasingly using sonar technology that surpasses satellite accuracy.

This mirrors nineteenth-century British emergency mapping between Russia and India. At that time, cartography and espionage were inseparable.

“Mapping and espionage were one and the same.”

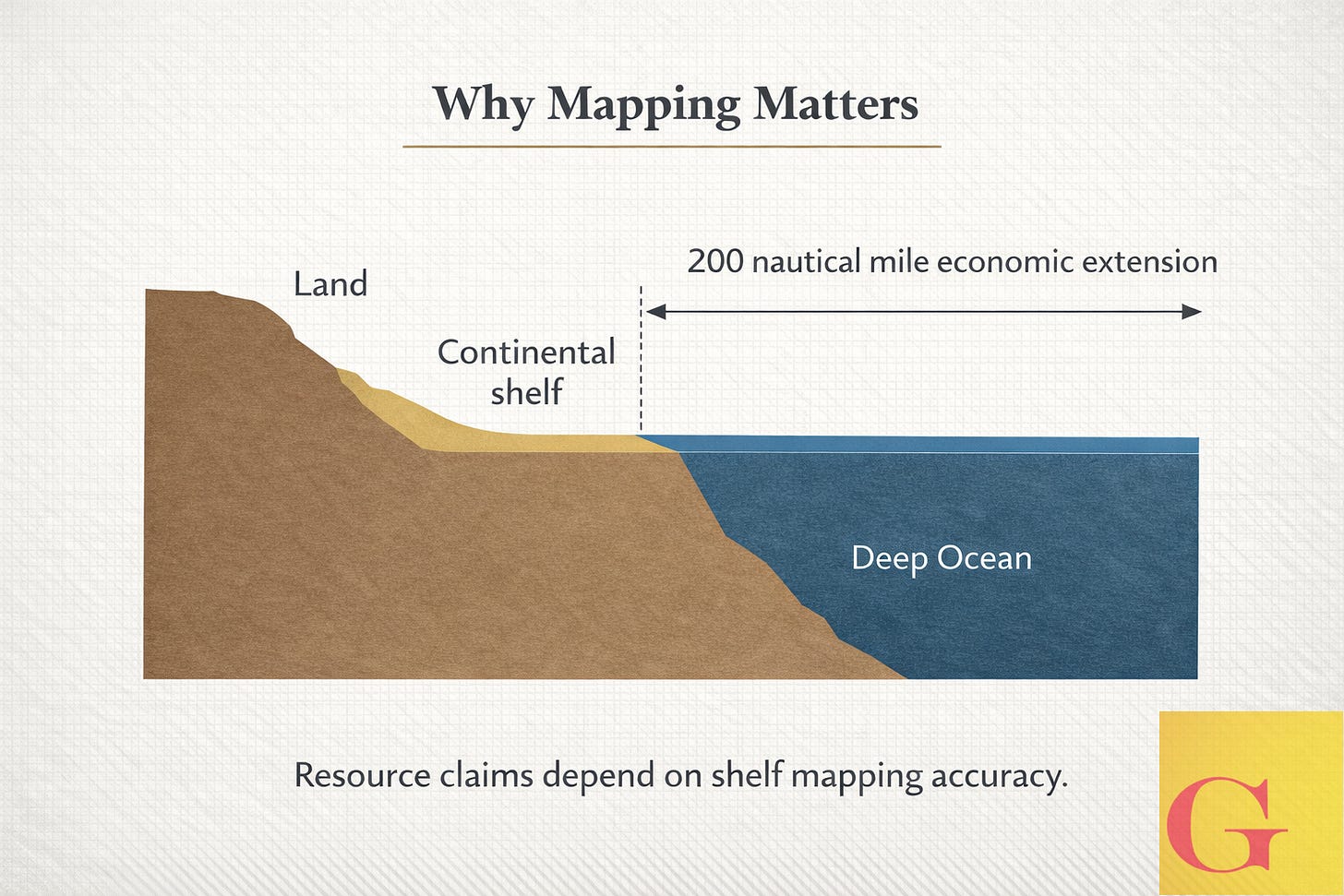

Today, the same principle applies. Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, countries can extend economic claims 200 nautical miles beyond continental shelves. Accurately locating those shelves determines access to future resource wealth.

The United States and Russia are actively conducting shelf surveys. China has gone further, reportedly sending submarines beneath Arctic ice during the past summer, likely serving both economic and defense purposes.

Mapping now supports both resource claims and cyber-strategic positioning, blending physical geography with digital control.

Mercantilism: Forward Strategy Without War

The modern great game emphasizes preemption rather than direct confrontation. The goal is to secure territory, alliances, and resource pathways before rivals can respond.

This forward strategy avoids formal war while generating constant tension. It produces shadow conflicts, buffer-state diplomacy, border disputes, and shifting coalitions.

Mercantilism('s) Rules

“Vince, mercantilism never stopped”- Fund Manager 2022

For the past three years, nearly every government behavior and policy change has been tied to one key concept: Mercantilism. Now's a good time to revisit what Mercantilism really means.

Textbook definition: Mercantilism emphasizes the importance of a favorable balance of trade and strong government control over economic activities to boost national power and wealth.

Historically, Mercantilism emerged after Feudalism's collapse and became less prominent with the rise of global trade. However, it's now resurging as globalized economies struggle to stay cooperative while globalism wanes. Read full story

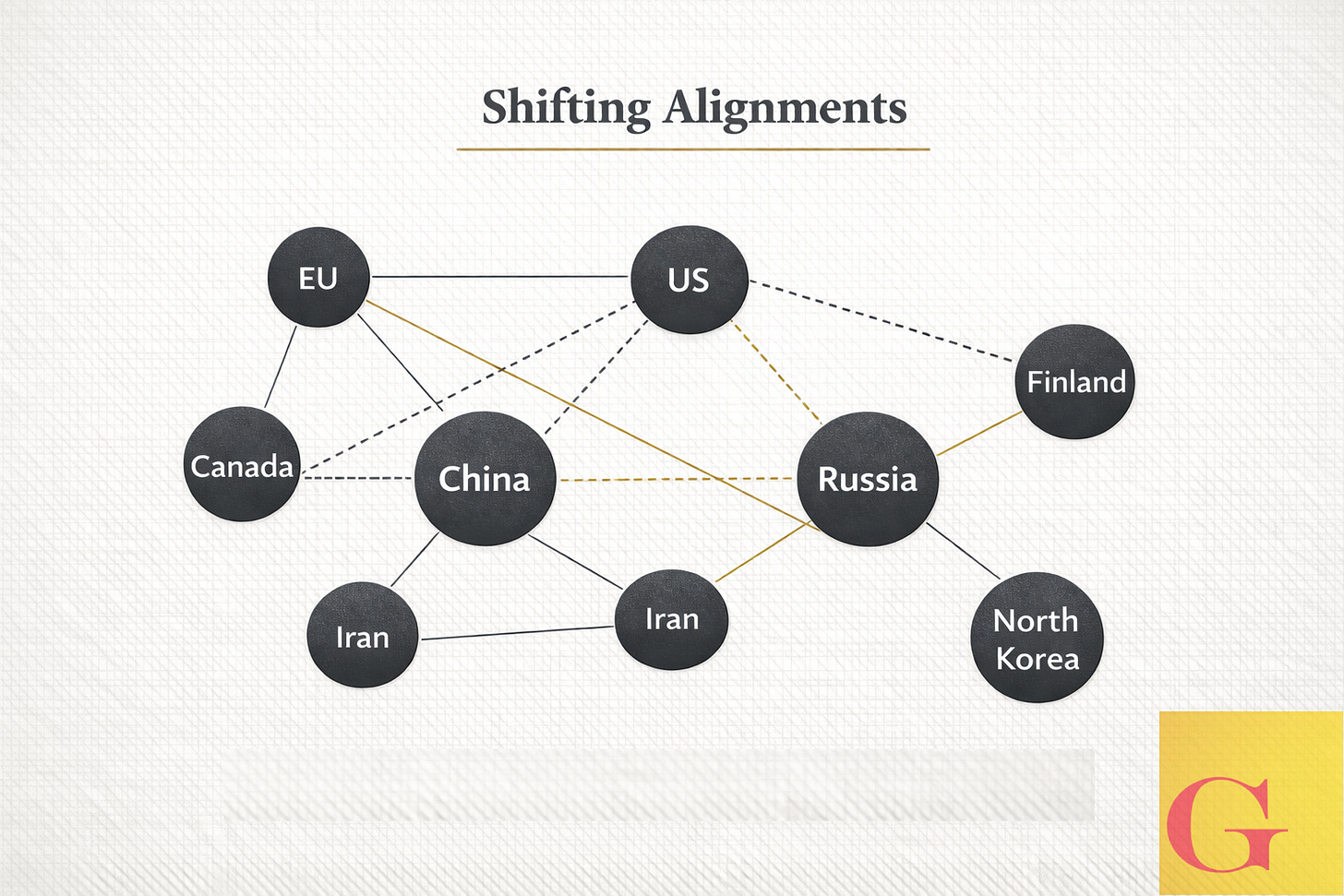

As in the nineteenth century, alliances remain fluid. Russia and France once fought both together and against each other. Afghan and Persian allegiances shifted repeatedly. Today, China and Russia cooperate in the Arctic. China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea form a loose anti-American axis. Yet these relationships remain fragile.

Trust, Mercantilism, and Why We Need Gold

Mercantilism has to work until trust is restored or the next step may be far worse. For mercantilism to work, trade collateral has to be unencumbered, unimpeachable, and not controlled by man.

Europe invented it and it saved them once before. Mercantilism is happening again between the US and China. The EU will be serfs for Klaus after the next World War if it fails this time. Trust will return, but not until everyone has earned it again. Read full story

Meanwhile, US alliances are also strained. Canada and Finland, nominal partners in shipbuilding and Arctic strategy, reflect the complexities of cooperation inside a mercantilist framework.

European divisions deepen the instability. European states differ on Venezuela’s political future and remain uncertain about how to respond should Greenland be annexed. Public support for military defense is weak across much of Europe, limiting political flexibility.

Like the original great game, today’s contest unfolds indirectly. Influence expands through economic pressure, infrastructure, diplomacy, and selective confrontation.

Multiple regions are implicated: Europe, Korea, Japan, Australia, Africa, and Latin America. None can remain neutral. Each must navigate non-binary choices between US and Chinese influence.

These decisions will not resolve quickly. The competitive framework is expected to persist for decades.

Peter Hopkirk’s historical assessment frames the modern moment with clarity:

“Some would maintain that the great game never really ceased, and that it was merely the forerunner of the cold war of our own times, fuelled by the same fears, suspicions and misunderstandings.”

Those same forces now define the present environment. Strategic competition continues under new labels, new technologies, and new geographies, but with familiar underlying dynamics.

Continues here goes to Scottsdale