Fuel Cells Poised to Capture 1/3 of Data Center Power Demand by 2030

From the TightSpreads Substack.

Goldman Sachs estimates that behind-the-meter (BTM) solutions could address roughly a quarter to a third of the incremental electricity demand from data centers, or 20-25 GW by 2030. The most promising technologies for this time frame are gas turbines and fuel cells, both capable of providing stable, dispatchable power independent of grid constraints. To assess power generation types, look across the following four areas:

- Levelized cost of electricity (LCOE)

- Time to market

- Noise from electricity generation

- Emissions

Fuel cells, particularly SOFC, are structurally advantaged for data center applications, offering higher efficiency, modularity and shorter lead times than gas turbines. GS estimates that fuel cells could supply 25%-50% of total BTM power demand by 2030, equivalent to 8-20GW of the installed capacity required to supply electricity.

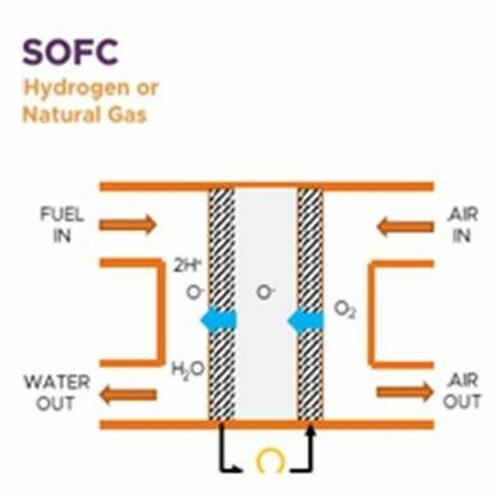

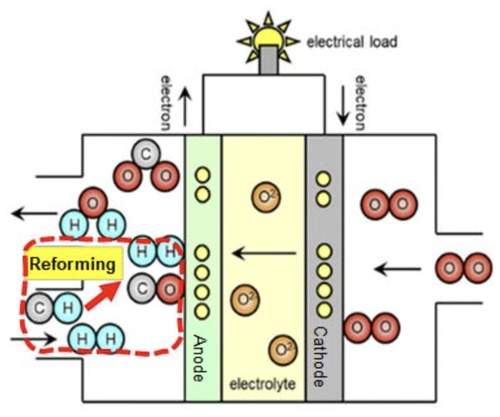

Fuel cells are functionally similar to batteries. However, their source energy comes from breaking the molecules of Hydrogen (H2) without combustion. A fuel cell does this through two electrodes —a negative electrode (or anode) and a positive electrode (or cathode) — between which is an electrolyte (a substance rich in ions that can conduct electricity). The hydrogen fuel is fed to the anode, while air is fed to the cathode. At the anode, a catalyst is present to turn hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons, which take different paths to the cathode. The protons migrate through the electrolyte to the cathode, where they unite with oxygen and the electrons to produce water and heat. The electrons will pass through a circuit, which creates the electrical current which is harnessed for power.

Natural gas (mostly methane, i.e., CH4) can also be used in fuel cells as fuel, but needs to go through a process called ‘Reforming’ to be turned into H2 and carbon monoxide(CO). For fuel cells that operate at high temperatures (SOFC, MCFC), this process could be done directly at the anode with a catalyst. Otherwise, natural gas needs to be reformed externally.

Fuels are fed to the anode and air is fed to the cathode to produce produce the electricity in a fuel cell.

Source: Ceres Power

The methane molecules are reformed at the anode to become hydrogen and carbon monoxide for fuel cells reactions.

Source: Royal Society of Chemistry, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

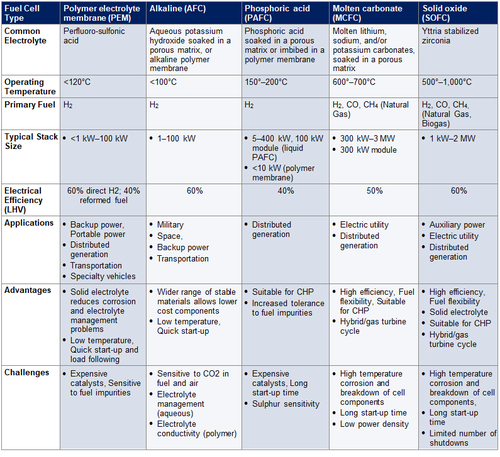

Fuel cells are primarily categorized according to the type of electrolyte they use. This classification influences the electro-chemical reactions within the cell, the catalysts required, operating temperature ranges, fuel types, and the limitations it has. These characteristics, in turn, determine the most suitable applications for each fuel cell type. Currently, several fuel cell technologies are under development. Judging by their operating temperatures, low- to medium-temperature type fuel cells include polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM), alkaline (AFC) and phosphoric acid (PAFC). They operate from a range of sub-100 degrees to 200 degrees, which means natural gas needs to be reformed externally to be used as fuel. Among these low to medium temperature fuel cells, PEM and AFC have the advantage of high energy density and efficiency, ideal for use in transportation, but are sensitive to fuel impurities. PAFC is bulkier and operates less efficiently, but it has a stronger tolerance to impure hydrogen, which makes it optimal for combined heat & power plants that reuse the excess heat. Molten carbonate (MCFC) and solid oxide (SOFC) operate at much higher temperatures, 600-1,000 degrees. Methane can be reformed in-cell to produce hydrogen and other gases, which allow them to run on natural gas, bio-gas and other methane rich gases. However, higher temperatures also mean longer start-up time, making them more suitable for sustainable power source rather on on-demand peaking supply. These units tend to have high fuel efficiency and large power capacity, suitable for power-hungry needs.

In practice, only SOFC and PEM are discussed as realistic applications in data centers, due to their higher fuel efficiency and commercial readiness. PEM has seen its application in automobiles for years, and SOFC has had significant production ramp up in recent years.

Comparing the Types of Fuel Cells

Source: Department of Energy

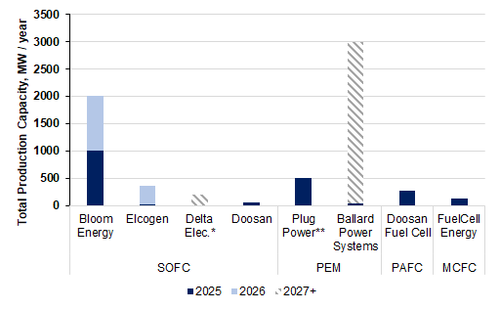

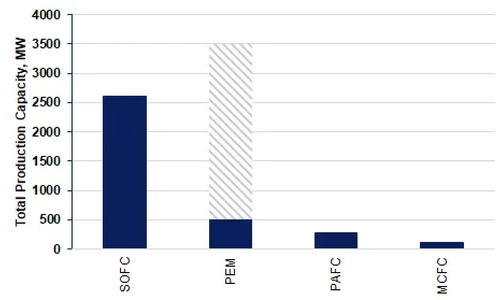

There is a significant near-term build up of capacity for fuel cell production

Total production capacity per year, MW

*GSe of Delta Electronics production capacity at 200MW per year; **PEM Ballard’s Giga-factory is pending FID in late 2026; Source: Company data, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

SOFC has the largest share of existing capacity and capacity under construction

Source: Company data, compiled by Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Fuel cells are extensively used for stationary power generation, providing reliable and efficient electricity for a wide range of commercial, industrial, and residential needs. They serve as primary power sources for buildings, hospitals, and factories, and as crucial backup power systems for critical infrastructure such as telecommunications, data centers, and emergency services with up to 99.9999% uptime. In addition, Fuel cells are particularly valuable in remote areas, including in spacecraft, remote weather stations and military outposts. They can also be integrated into micro-grids, providing autonomous power generated from renewable energy sources stored as hydrogen. Because of the heat generated, many stationary fuel cell systems are designed for combined heat and power (CHP) or cogeneration, simultaneously producing electricity and useful heat.

Fuel cells offer compact, lightweight, and efficient power solutions for portable and mobile applications. Direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) and other small-scale fuel cells are being developed to power consumer electronics such as laptops, smartphones, and cameras, offering higher energy density and longer operating times.

Fuel cells are a key technology for decarbonizing the transportation sector, offering zero-emission alternatives to internal combustion engines. Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) use hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity for an electric motor, producing only water vapor as a byproduct. This category includes cars, buses and utility vehicles. Fuel cells can also be deployed on trains, ships and, especially lighter aircraft, where they are considered one of the few solutions for low-emission flying.

At its core, SOFC technology can be used to convert fuels such as hydrogen into electricity (fuel cell) and vice versa (electrolyser). The SOFC technology has been successfully deployed in fuel cells and is currently one of the most advanced technologies in the space (along with PEM and alkaline). SOFCoffer two key advantages compared to the competing technologies:

Much higher operating temperature (>500°C) enables them to generate electricity from a range of different fuels, including natural gas, biogas, hydrogen blends and hydrogen

Benefits from superior electrical efficiency.

Comparing Bloom Energy and Ceres Power technologies:

As of today, there are three types of SOFC technologies that are commercially ready. In order of development, these are: (1) Electrolyte-supported (ES-; 1st gen); (2) Anode-suppported (AS-; 2nd-gen); and 3) Metal Supported (MS-; 3rd-gen). These are respectively produced by: (1) Bloom Energy; (2) Elcogen; and (3) Ceres Power, for their successful commercial deployment in the industry. The difference between the types lies in the supporting structures in the fuel cells that give the cells structural integrity. A component of the cell is usually thickened to provide support. In an ES-SOFC, the electrolyte, made from ceramics is used as the supporting structure; in AS-SOFC, the anode layer is thickened as support; however, in an MS-SOFC, an external steel structure is built in.

ES-SOFC is considered the first generation of SOFC, giving Bloom a clear head start with commercialization. With the thick ceramic electrolyte layer made from doped zirconias (a synthetic ceramic material used in all SOFCs for its ability to conduct oxygen ions), ES-SOFC technology needs a higher operating temperature of around 800-1,000 oC. This is due to doped zirconia’s lower conductivity, which improves as the temperature gets higher, while the thicker electrolyte layer requires a higher external temperature to maintain its inner temperature. The thick electrolyte layers also means that the structure has lower power density and a higher production cost reflecting the rarity of the zirconia ingredients. Bloom Energy is widely regarded as the leading player in the global SOFC market, because of its large installed capacity, close to 1.5 GW worldwide. It is a vertically integrated developer and producer of electrolyte-supported SOFCs (ES-SOFC).

The second generation of the technology, AS-SOFC thickens the anode instead of the electrolyte. The anode and electrolyte are both made from zirconia, but the anode has a porous structure while the electrolyte is impermeable. This means heat can disseminate more easily even as the anode is thickened, which allows for a lower operating temperature than ES-SOFC. As a result, AS-SOFC runs with higher efficiency. However, the higher material cost still persists from the thickened anode. Elcogen, a private Estonian company, produces the technology, with recently expanded production capacity of 360MW per year.

The third generation, MS-SOFC, builds an external porous steel structure as the support of the fuel cells. Steel is much cheaper to produce, and it uses much thinner cathode, electrolyte and anode layers made from expensive materials. Steel is also a better conductor of heat, which further lowers operating temperature. Metal is more ductile than ceramics materials, which makes the structure more durable in high-temperature, high-pressure environments. Ceres Power is an emerging developer of the technology, beginning as a spin-off from Imperial College London.

The remaining comes from Goldman’s latest fuel cell market report:

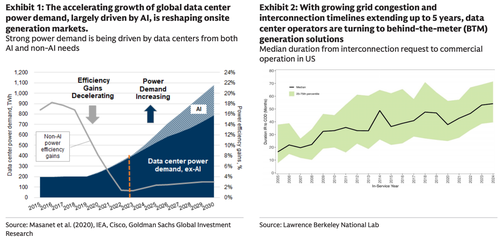

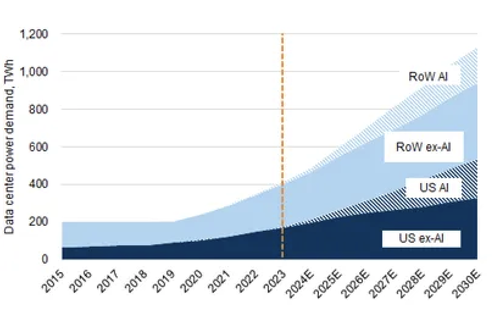

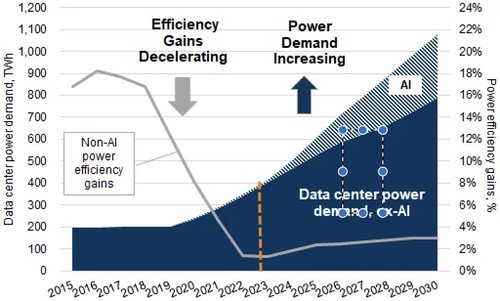

AI investment and legacy data demand continues to grow: our US team now sees global power demand from data centers -- AI + non-AI -- growing 175% in 2030, vs. 2023, the equivalent of adding another top-10 power consuming country. Our US Utility team forecasts data centers accounting for ~120 bps of growth within the overall 2.6% US power demand CAGR (to 2030E) that they see. They assume ~82 GW of capacity will be needed to meet this data center demand, up from 72 GW previously.

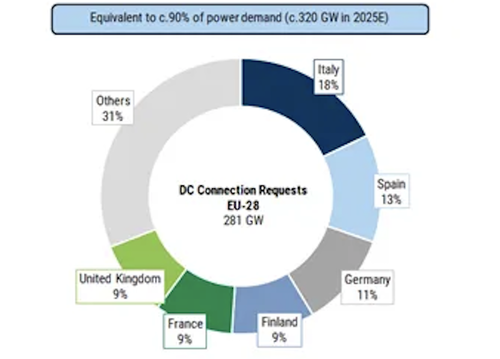

According to our European utilities team, demand for data center (DC) connections to the European power grid is also booming. They believe that this is likely a prelude to a substantial build-out, which should provide a significant tailwind to power consumption. Based on the team’s discussions with the main grid system operators in Europe, they estimate a data center pipeline of c.280 GW presently. Although only a portion of this total might be converted, this pipeline is substantial, equivalent to c.90% of current power demand in the EU28 (c.320 GW), and indicating a strong outlook for power consumption.

This rapid growth strains grid systems, which struggle to keep pace, while data centers compete with other industries for limited electricity supplies amid environmental compliance pressures. Data centers pose unique challenges to electricity grids, compared to other types of energy users. They represent large, localized loads which typically operate continuously and can ramp up their operations faster than most large energy users.

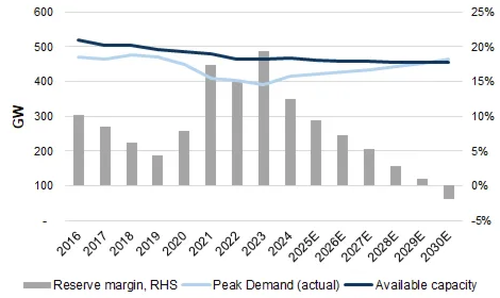

Europe’s power grid is increasingly constrained, limiting new data center projects, especially in key FLAP-D markets (the largest capital hubs for ICT), where grid saturation has already led to restrictions on new data center connections until at least 2030. According to our European Utilities team, Europe’s reserve margin - the excess of available generation over peak demand - is heading toward a negative level, as available capacity looks set to fall below peak demand by 2030E.

Globally, Bloom has said it sees accelerating opportunities, owing to tightening power supply. In Europe, energy shortages and transmission bottlenecks have made it difficult for central power plants to keep up with the rapid growth of AI workloads. The same trend is evident in India, where Delhi and Mumbai face similar constraints. Management has described a shift in sentiment in Asia - particularly in Japan - where natural gas is increasingly viewed as not just a short-term bridge fuel but long-term part of energy mix supporting energy security and decarbonisation.

After being flat through 2015-19, we have seen data center power demand...

Strong power demand is being driven by data centers from both AI and non AI needs.

Source: Masanet et al. (2020), IEA, Cisco, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

…. accelerate in 2021-23 and expect a ~175% increase through the rest of the decade

Global datacenter electricity consumption, TWh; includes AI and excludes cryptocurrency

Source: Masanet et al. (2020), Cisco, IEA, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

European utilities have received c.280 GW of connection requests from data centers.

European data center connection requests, geographic region (GW, percentage)

Source: Company data, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Europe’s reserve margin is heading toward negative territory with available capacity being lower than peak demand by 2030E.

Europe power generation demand vs. capacity

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

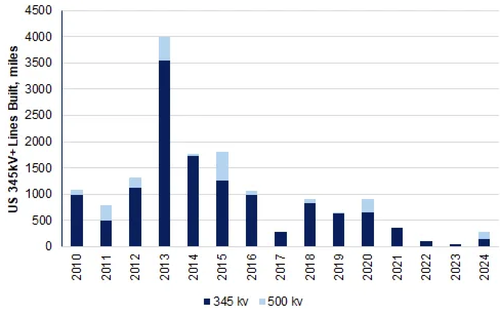

Construction of new high-voltage transmission lines has continued to slow.

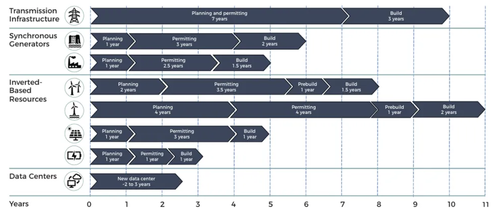

Connecting data centers to the grid is a complex and often lengthy process, reflecting several critical factors. The surge in demand for data centers has overwhelmed existing grid infrastructure and planning processes.

The primary reasons for delays:

Insufficient transmission and generation capacity: The fundamental issue is a lack of adequate transmission infrastructure and generation capacity to meet the continuous, high-utilization power demands of data centers. Data centers require round-the-clock power comparable to small cities. Building new transmission lines and generation facilities involves years of permitting, land acquisition, supply chain management, and construction, typically (5-10 years). The pace of new high-voltage transmission line construction in the US has significantly declined, from an average of 1,700 miles annually between 2010 and 2014 to just 350 miles per year from 2020 to 2023. Only 55 new miles of high-voltage transmission were constructed in 2023. According to the FERC Energy Infrastructure Updates for 2024, only 125 new miles of high-voltage transmission have been constructed from January 2024 to May 2024. Additoinally, new generation is not being built fast enough to keep up with load growth.

Outdated planning tools and processes: Utility planning tools and processes were not designed to handle the current scale of growth, particularly the influx of numerous large load requests from data centers. Planners are often overwhelmed, and unlike generation interconnection, the process for evaluating large loads is frequently ad hoc, lacking well-defined steps. This inconsistency makes rapid and fair project evaluation difficult and can lead to speculative applications flooding the queues, further exacerbating backlogs.

Conservative utility planning assumptions: Utilities often evaluate interconnection requests based on worst-case scenarios, such as peak system demand and N-1 or N-2 contingencies (loss of a major component), with the data center operating at full load. These conservative assumptions can lead to feasible projects being deemed too risky, forcing them to wait for extensive infrastructure or generation build-out. This approach primarily focuses on the supply side (generation and transmission) and often overlooks opportunities for flexibility.

The pace of new high-voltage transmission line construction in the US has significantly declined, from an average of 1,700 miles pa between 2010 and 2014 to just 350 miles pa from 2020 to 2023.

US transmission lines built, miles

Source: Grid Strategies

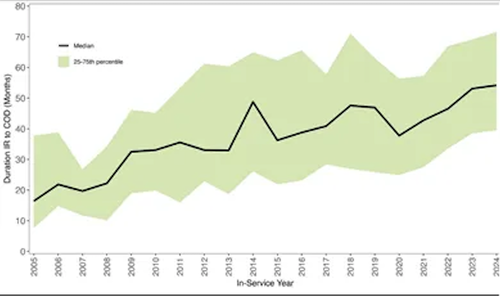

The median duration from interconnection request (IR) to commercial operations date (COD) continues to rise, approaching 5 years for projects completed in 2023-2024.

Median duration from Interconnection request to commercial operations in the US (apologies for blur)

Source: Lawrence Berkeley National Lab

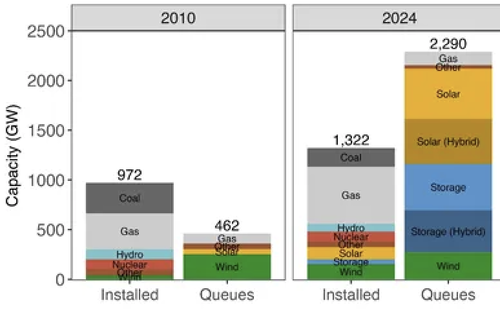

Active capacity in queues (~2,300 GW) is almost twice the installed capacity of US power plant fleet (~1,320 GW); greater than peak load and installed capacity.

Entire US installed capacity vs. active queues

Source: Lawrence Berkeley National Lab

Illustrative time to market for various grid projects

Source: GridLab

Around a quarter of incremental data center demand through 2030E might be met by BTM solutions.

As grid capacity becomes less available, and congestion and connection times ramp up, industry participants are turning to new markets. To mitigate these delays, a hybrid approach, combining grid power with on-site generation or battery storage, is gaining traction. This ‘flexible interconnection’ allows data centers to reduce their demand on the grid during stressed periods without impacting server operations, potentially accelerating connection timelines by years.

BTM solutions have become more relevant in 2025 when increasing power demand from data centers, due to the surge in AI, has exceeded the typical handling capacities of the grid. BTM solutions leverage energy generation and storage technologies to power electricity demand from the end users’ vicinity, with energy consumed directly without passing through the utility meter and the grid. They offer an important alternative means of ensuring uninterrupted operation, insulated from the vulnerabilities of the grid. According to our GS Sustain Team, incremental electricity demand from data centers should total c.730 TWh over 2024-30E, reflecting the rapid expansion of AI workloads and digital infrastructure. If a quarter to a third of this is BTM met, this suggests that up to 25 GW of BTM generation will be deployed over the next five years. Some of that will likely be as gas turbines, diesel engines, renewables and storage, and some may be nuclear. However, fuel cells are expected to play a crucial role, offering data centers a scalable, sustainable on-site power solution as AI and cloud computing drive unprecedented energy demand. Given the huge gap between supply of and demand for BTM solutions, any technology that has reached commercial readiness and expandable capacity should see adoption with less price sensitivity, we believe. We estimate that 25%-50% of total behind-the-meter power generation supply could ultimately be provided through fuel cells, which would correspond to roughly 8-20GW of fuel cell capacity required to supply electricity by 2030.

There are several technologies that offer behind-the-meter characteristics, including on-site generation, energy storage, microgrids, combined heat and power systems etc. Specifically for the needs of data centers, there are three main factors influencing the decision on the appropriate solutions: (1) the levelized cost of electricity; (2) power consistency and flexibility; and (3) power density and cleanliness.

Levelized cost of electricity is the average cost of the electricity aggregating the upfront investments needed and the units costs to generate electricity over its useful life (see note here). Power consistency and flexibility measures how reliable and agile a grid is, respectively responding to the requirements of high up time for reliability, and fast start-up time to handle surges in demand. Power density refers to the capacity of the power source relative to the area it occupies, while power cleanliness is the level of pollution it generates. These are relevant for dense urban centers where space is constrained and environmental regulations are stringent.

Based on the criteria, the viable BTM solutions for data centers range from onsite generation through gas turbines, fuel cells, diesel engines, solar and SMR and geothermal plants, to energy storage system using batteries (BESS). Onsite generation will likely be used to handle longer-term electricity demand as grid infrastructure builds, while BESS responds to the short-term need for back up and load balancing.

Gas Turbines are internal combustion engines that convert fuel, such as natural gas or hydrogen, into mechanical energy. This process involves compressing air, mixing it with fuel, and igniting the mixture in a continuous combustion process. The resulting high-pressure gases then spin turbine blades to generate power.

Diesel Engines are internal combustion engines that ignite fuel by compressing air to a high temperature, rather than using spark plugs like gasoline engines. They are widely used for electricity generation, particularly for backup power, in remote locations, and for mobile power supply. They have relatively small power output and consume large amount of diesel in the long run which makes them ideal for back up power.

Solar power generation harnesses energy from the sun and converts it into electricity. It generates intermittent electricity, depending on the weather, making it more suitable for supporting the base load. It could also be paired with BESS for more consistent power supply.

BESS is a technology-based solution that utilizes rechargeable batteries to store electrical energy for later use. The systems gather energy from diverse sources, including renewable and conventional power, and discharge it to supply power during peak demand, outages, or for grid stabilization.

Small modular reactors (SMRs) and geothermal plants harness nuclear and geothermal power to generate electricity. They are reliable and relatively cheap over the long run. However, owing to their long investment cycle, the majority of the investments from data centers are unlikely to result in their realization before 2030.

Fuel cells and gas turbines serve the base load of onsite electricity demand, while diesel engines, solar and BESS are suitable for base load support and backup power based on their size and generation pattern.

Source: Company data, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Comparison of fuel cells and gas turbines

1) LCOE: Fuel cell LCOE remains c.40% above gas turbines, yet costs are expected to converge

In this report, we have compared the LCOE from fuel cells and conventional power plants, using natural gas as a fuel. This comparison includes the LCOE of simple-cycle and combined cycle gas turbine plants against the LCOE of SOFC fuel cells.

From an LCOE standpoint, gas turbines currently offer a cost advantage, owing to a mature supply chain and economies of scale, especially in combined-cycle configurations where efficiencies reach 55%-62% (higher heating value - HHV). However, fuel cells, particularly SOFC and PEM systems deliver higher efficiency (up to 62%-65% HHV) and improved part-load performance, which can offset higher upfront capital costs over time.

We estimate the LCOE of fuel cells to be in the range of 130-205 $/MWh (natural gas at 4$/MMBtu) and 150-225 $/MWh (natural gas at 8$/MMBtu), depending on the investments costs and load factors. Since fuel cells have a high share of capex in total costs, achieving higher load hours greatly improves their economic performance. When heat generation is monetized through combined heat and power (CHP) applications, the LCOE can decline further to around 120-200 $/MWh (natural gas at 4$/MMBtu) and 135-215 $/MWh (natural gas at 8$/MMBtu). Fuel cells are characterized by high electrical efficiency (55%-65%), stable performance at partial load, and minimal maintenance requirements. However, their high capex (we assume a base-case fuel cell system cost of around 6,000 $/kW) remains the main cost driver. Market ramp-up of fuel cell technologies, combined with learning effects and supply chain maturity are projected to lower investment costs and increase load factors over the coming decades. As deployment scales, the US Department of Energy (DOE) established a 2025-2030 system capital cost target of $900/kWnet.

By contrast, gas turbines, both simple-cycle and CCGT, have lower upfront costs but higher fuel-related expenses and lower efficiency in small-scale setups. However, in the meantime, gas turbines have become more expensive as a result of excess demand in the market, with key producers GEV and MHI seeing steady margin expansion. Similarly, the construction cost of gas power plants has risen in recent years. Combined cycle plants have reached $2,000-2,200 / kWh in 2025, compared to $1,300 / kWh in 2023. Those scheduled for delivery beyond 2030 cost closer to $2,500 / kWh. This upward trend in turbine costs contributes to the improvement of the relative attractiveness of fuel cells vs. gas turbines. We estimate CCGT/GT LCOE values generally fall in the range of 40-90/90-185 $/MWh (natural gas at 4$/MMBtu) and 60-115/130-225 $/MWh (natural gas at 8$/MMBtu), respectively depending on the capex and load factors.

Overall, fuel cells currently have a higher LCOE than gas turbines - roughly 40% higher than that of simple-cycle gas turbines. The cost gap is mainly driven by the high cost of fuel cell systems and limited deployment scale. However, as manufacturing expands, we expect the LCOE of fuel cellsto improve substantially, gradually approaching the competitiveness of advanced gas turbine technologies in the longer term.

2) Time to market: Gas turbine lead times have stretched to 5-7 years, while modular fuel cell systems can be deployed in less than a year

Global demand for large gas turbines has surged, leading to record-long delivery backlogs, driven in large part by the explosive growth of data center and AI-related power generation projects. Manufacturers such as Siemens Energy, GE Vernova and Mitsubishi Power report that orders from data center developers now account for more than half of their current pipeline, pushing lead times from the pre-pandemic norm of 2-3 years to as much as 5-7 years for new turbine units.

Record demand for utility‑scale gas turbines has extended order backlogs and stretched delivery windows. Across OEMs, commitments now span multiple years, with capacity expansions only gradually easing constraints from 2026-27E onward. Recent company and industry disclosures indicate delivery windows to 2029-30 for certain large‑frame projects, with industry reports citing cases up to seven years depending on scope and permitting.

The world’s most important gas turbine producers are GE Vernova, Siemens Energy and Mistubishi Heavy Industries. They have seen a record level of orders in the last two years as power demand has increased substantially. To facilitate this unprecedented surge in power demand and hence turbine needs, all three companies have announced plans to scale up their production capabilities. However, the capacity increase seems unlikely to materially change the tight market conditions. GE Vernova guides to an end of year backlog of 70GW, with increased capacity of 20GW coming online by 2H26, giving an implied lead-time of 4-5 years from now. Siemens Energy has built up a backlog of 37GW with 21GW of reservations, and expects to ramp-up its production rate to 20GW per year in 2026, which gives an implied lead-time of 3-4 years from now. Siemens Energy has also fully slotted orders for delivery in 2029. Mitsubishi guides for new products entering service in 2029-2030.

Under normal market conditions, gas turbines are faster to deploy than fuel cells: one-cycle GT can be commissioned in 12-18 months and CCGT in 18-24 months. Fuel cells, particularly SOFC and PEM systems, have typically required 18-30 months, reflecting lower production volumes and custom integration needs. Today, however, this dynamic has shifted. As mentioned above, gas turbine lead times have been pushed up to 5-7 years, while fuel cell systems from Bloom Energy can be delivered and installed within 6-12 months for modular projects of up to 10 MW, per the companies. Even at larger scale, their timelines remain more predictable than the heavily backlogged turbine market.

3) Noise from electricity generation: Fuel cells offer near-silent operation vs. high-noise gas turbines

In terms of noise, gas turbines operate within a range of 90dB to 120dB, at a high frequency similar to that of a jet engine. There can also be significant burst sounds at startup, and vibration is likely to follow as it operates. These could be challenging factors when considering setting up onsite power close to business or residential areas. Fuel cells on the other hand are nearly completely silent, free of any moving components, making them more neighborhood friendly, and aligning well with urban noise-control standards and ESG priorities. For data centers, this translates into a major advantage: fuel cells can be sited directly adjacent to buildings or even indoors, while gas turbines require dedicated acoustic treatment and separation zones.

4) Emissions: Fuel cells deliver cleaner power with lower emissions

Another important consideration for onsite power is air pollution. Compared to fuel cells, gas turbines rely on a dirtier combustion process to harness methane’s chemical energy. This creates a high-temperature environment where nitrogen in the air is oxidized. In the case of incomplete combustion, turbines could produce carbon monoxide. This is an important distinction between gas turbine and fuel cells: the operating temperature of SOFCs, around 600 Celcius, is too low to produce NOx, nor is there combustion to create CO, which is especially harmful in an urban setting where data centers are located. The two have similar levels of carbon intensity, with Ceres’ SOFC and GEV’s turbine in a combined-cycle setting boasting greater than 60% fuel efficiency, meaning 60% of the chemical energy of the gas consumed is being converted into electricity. This translates roughly into 330g of CO2-eq/kWh of electricity generated.

5) Load versatility and data center HVDC power trend

Fuel cells are excellent at producing more or less power in the face of changing load demand. They do not possess the mechanical combustion parts that restrict them to operation within a certain range. For instance, a gas turbine generator should operate above 40%-50% of its total capacity as operating at a lower load leads to higher NOx emissions. Fuel cells can be operated within a wider range because of their modular design, responding to the needs for electricity more rapidly.

Nvidia is pushing for a new 800V high-voltage direct-current (HVDC) design for electricity transmission from grid to data center stacks. This reflects the limitations of the current 54V AC (alternating current) infrastructure that requires large transformers and thicker copper cables, which are both space-consuming and uneconomical. Fuel cells produce DC (direct current) electricity which bypasses these limitations and can be easily connected to an 800V HVDC system. These advantages further underpin the competitive position of fuel cells for data center power demand.