Read Financial Statements Like a Hedge Fund Analyst

From the TightSpreads Substack.

A company’s financials come in three statements: income statement, balance sheet, and cashflow statement. The three statements allow investors to assess whether the company profitable (income statement), financially stable/levered (balance sheet), and if they can fund operations and growth without excessive dilution or debt (cash flow). The following is an detailed explanation of how I would read over the financials of a company to better understand their business, and how to calculate profitability metrics and their significance.

Income Statement

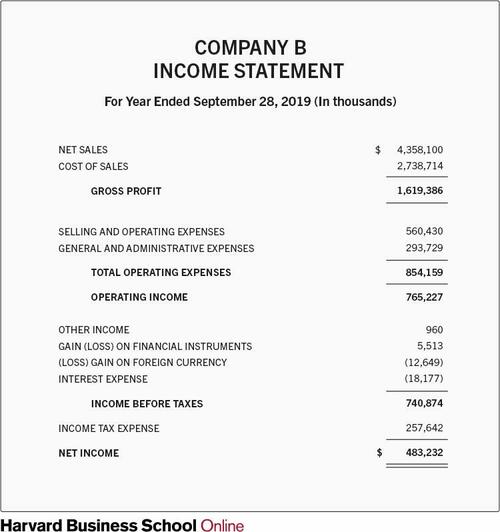

The income statement shows the profitability of a company over a period of time (quarters, years). The first section is called your ‘top line’ which is revenue. Revenue is the sales of products and services. Look for their revenue growth rate. Think about how this fits in relation to management’s and your own assumptions on their demand profile and market outlook. Changing trends here can indicate a volatile business or cyclicality. Ideally your company has a consistently positive growth rate that is growing over time. Identify what drives this growth.

Cost of good sold (COGS) follows revenues, showing you what it costs to produce the revenue which gives you a gross profit. Gross margin is the profitability metric, it’s going to be impacted by either sales (lower or higher pricing) or COGS (increasing or decreasing costs). Rising gross margins indicate benefits of scale or pricing benefits.

EBITDA = earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. We deliberately excludes those four items to isolate core operating profitability from factors that are largely outside operational control or introduce noise/comparability issues in analysis (more on in the appendix). EBITDA is simply gross profits - cost of operations (excluding non-cash charges, depreciation and amortization). Cost of operations include sales and marketing, research and development, and general and administrative costs. These are varying budget expenses that allow the company to operate in dynamic industry and market conditions in the context of their business strategy. EBITDA margin shows you the cash profit margin of a business. Compare EBIT and EBITDA margins to get a sense of the depreciation and amortization costs of the business. If there is significant depreciation and amortization, use EBIT. A good company should have positive operating margins. This indicates profitability and lowers the likelihood for the business to raise capital, which dilutes your earnings per share. When a company sells shares, they increase the shares outstanding of the same profit pool. Conversely, a profitable business will fund their own growth through their earnings.

How to compare gross and operating margins to see the source of efficiencies within a company:

If a company has stronger gross margins but stable operating margins, they’re realizing stronger pricing or efficient costs. Gross margin expansion is often the highest-quality, most durable form of profitability improvement because it flows directly from core product economics and competitive moat; it’s harder for competitors to replicate quickly than SG&A cuts. However, if operating margins remain flat despite gross gains, it suggests operating expenses (especially sales & marketing or R&D) are growing in line with or faster than gross profit—potentially heavy reinvestment phase, inefficiency in overhead, or deliberate growth spending. Watch whether this reinvestment translates into accelerated revenue growth; otherwise, it risks margin dilution over time.

If a company has stronger operating margins but stable gross margins, this signals operating leverage* kicking in (fixed costs spread over higher revenue) and disciplined cost control in overhead—often a hallmark of mature, scalable business models where incremental revenue drops more to the bottom line. This indicates improving operational efficiency and potential for higher free cash flow conversion without relying on pricing or COGS wins; this is especially powerful in software, services, or asset-light models. It can support sustained earnings growth even in flat/ modest revenue environments and often commands premium multiples. However, if gross margins are stable (or declining) due to competitive pressure or input inflation, the op-ex discipline may only be masking underlying weakness in the core business—long-term sustainability depends on whether gross margins stabilize or rebound.

*Driving top line and then eventually higher operating margins is called operating leverage. This is the tailwind effect of scaling a business. Sometimes margins go down when business growth slows, that’s considered negative leverage. Be sure to compare a business’ margins and their own growth rates in different market/industry/economic environments. A well run business would be able to weather different environments without too much fluctuation in their margins.

Net income is operating profits after subtracting interest and taxes. This is true earnings generating that belongs to shareholder. We need a close to, or already positive net income. The margin here is less important, I’d prefer companies to prioritize improving gross and operating margins. Companies could try to reduce interest and tax expenses.

Diluted earnings per share (EPS) is net income divided by the total shares outstanding. We want higher EPS by increases net income without needing to raise equity (when compared to raising debt. Raising equity is done by selling NEW shares) to finance operations. Growth in EPS is the most important metric on the income statement for an investor. If our share value (EPS) today will not grow in the future, then there is no point in investing without returns.

POSITIVE SIGNS IN THE INCOME STATEMENT:

STEADY REVENUE GROWTH

POSITIVE AND EXPANDING GROSS AND OPERATING MARGINS

GROWTH IN EPS

NEGATIVE SINGS IN THE INCOME STATEMENT:

DECLINING REVENUES

NEGATIVE OR CONTRACTING GROSS AND OPERATING MARGINS

DECLINE IN EPS

Balance Sheet

A snapshot of financial position at a single point in time. It lists what the company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the residual claim of owners (shareholders’ equity).

To understand the stability of the business, I first start by looking at their cash & equivalents and how that trends overtime. Hopefully a positive trend shows they’re generating that cash itself, but if it is in decline that raises two concerns over profitability and future financing needs (raising more debt / equity, possibly further diluting our earnings).

After looking at cash I move onto long-term debt. Debt represents financial risk for stockholders, and is a source of financing for a company’s operation. If a company cannot pay its interest or debt, it goes into bankruptcy. Debt holders will take control of the company, possibly leading them to sell all of the assets to salvage any returns on the company. This leaves equity owners last in line for repayment. The net debt (total debt - cash) should be looked at relative to EBITDA. I like this ratio to represent how many years of cash earnings it will take for a company to repay its debts. A net debt to EBITDA ratio of <2x is safe, anything >4x is riskier. A lot of the cash the company will generate when debt levels are that high, will be directed to debt holders and makes it hard to grow their equity otherwise. As debt is borrowed money, via bank loan or debt investment, we can also look at additional paid in capital to see how many shares the company is selling to raise capital and their retained earnings. Retained earnings is cumulative net income, it allows us to understand how a company has historically generated profits. Negative retained earnings could identify an unprofitable company, but look to the trend of this figure to see how they have improved their net income generated overtime. Ideally, capital comes mostly from retained earnings. This would reflect a profitable company that is able to fund their own operations. The only alternative to funding operations is from raising capital (via debt or equity) which will dilute your earnings per share as a stockholder. Again, raising equity directly dilutes EPS mechanically by increasing shares outstanding whilst the return on invested capital (ROIC) takes time to materialize in the company to make their future net income rise enough to make the EPS accretive over time. Debt financing will not immediately dilute EPS to the extent that equity will, but the interest expense will reduce your net income and therefore dilute EPS if after-tax cost of debt exceeds the incremental ROIC. Tax shields help as an interest deductible, so effective cost is lower, but mandatory interest still eats into earnings regardless of performance and poses financial risk.

The rest of this article is available to Premium Subscribers.