Social Security Will Be Insolvent In Six Years. What's Congress Going To Do?

Authored by Mike Shedlock via MishTalk.com,

Congress last made major Social Security changes 43 years ago...

The Wall Street Journal reports The Next Class of Senators Won’t Be Able to Dodge the Social Security Crunch

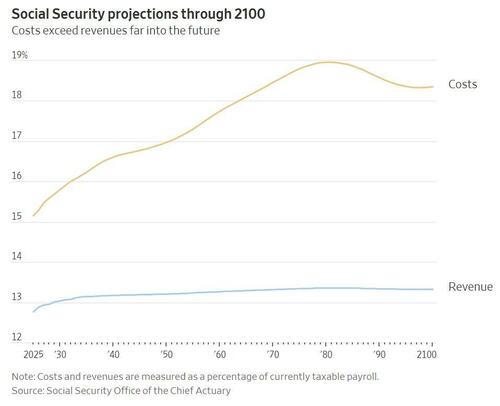

After years of Congress sidestepping and postponing the issue, the lawmakers will have to confront the program’s challenges before their new six-year terms conclude. Recent projections pegged late 2032 as the moment when Social Security’s reserves and incoming tax revenue won’t yield enough money to pay full benefits.

Failure to act would trigger automatic benefit cuts. Acting is no picnic either, because raising revenue or reducing promised payments could be politically painful.

The math is brutal for the program known for many years as the third rail of American politics. Social Security owes lifetime benefits to the huge generation of baby boomers who are already retired or almost there. That commitment locks in costs that are virtually impossible to dislodge and puts younger workers and future retirees on course for tax increases, benefit reductions or both.

Congress last made major Social Security changes 43 years ago in a less partisan Washington, staving off insolvency with just months to spare by adopting tax increases and benefit cuts intended to make the program last 75 years. Since then, Americans have been bracing for more changes, with polls showing many doubt they will get their full checks.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.), seeking his fifth term this year, said the 1983 agreement between Republican President Ronald Reagan and Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill is the model.

“I’m willing to do my part,” Graham said. “You’ve got to look at age adjustments, you know, means-testing benefits. You’ve got to put it all on the table.” Asked about taxes, he repeated: “All on the table.”

President Trump has repeatedly ruled out Social Security benefit cuts, breaking from many Republicans’ openness to the idea. The debate has been mostly dormant for a decade, and the program now requires larger changes to preserve solvency because smaller options that accumulate over time no longer yield enough money.

Huge program runs short

Congress and Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt created Social Security during the Great Depression to prevent poverty among older Americans; it is now the largest federal program. In the latest fiscal year, the U.S. paid $1.6 trillion in Social Security benefits, which is 22% of federal spending and almost double the military budget.

Social Security is funded largely with payroll taxes split between workers and employers. People receive payments after retiring or becoming disabled, getting amounts linked to their earnings history. The program also pays survivor benefits to spouses and children of workers who die. The average monthly retiree payment is about $2,000.

Tax increases and benefit cuts?

Social Security is excluded from the simple-majority budget process Congress used for recent partisan fiscal laws such Trump’s tax cuts, meaning any bill would require 60 votes in the Senate. Any durable bipartisan solution will likely have tax increases and cuts to future payouts.

There is no shortage of ideas. On the tax side, the prime target is the cap on the 12.4% payroll tax. Currently, wages and self-employment income above $184,500 are exempt from the tax, with the figure rising annually with inflation. That tax now covers about 83% of earnings, down from about 90% just after the 1983 changes.

Just eliminating the cap would cut Social Security’s long-run deficits in half. Taxing earnings above $250,000 and tying no new benefits to those earnings would remove about two-thirds of the shortfall, but that approach would change Social Security’s basic architecture that links taxes paid with benefits earned. Both options would sharply raise top marginal tax rates.

Raising the cap and devoting the money to Social Security is probably one of the few palatable ways Congress could get significant revenue from high earners outside the top 1%, said Kathleen Romig, director of Social Security and disability policy at the progressive Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

On the benefit side, the system is progressive, replacing a greater share of income for workers with lower lifetime earnings than higher earners. Lawmakers trying to protect people who rely on Social Security as their main income source could alter calculations so higher earners get less money than under current rules.

“It makes sense to rethink what the benefit formula looks like,” Romig said, especially because higher-income retirees likely have significant savings in 401(k)-style plans.

Lawmakers could also increase the basic retirement age. The 1983 changes pushed that to 67 from 65. Romina Boccia, director of budget and entitlement policy at the libertarian Cato Institute, said she would keep that going up to 70, then link the retirement age to longevity.

Other ideas are out there too. Sen. Bill Cassidy (R., La.) is pitching a $1.5 trillion sovereign-wealth fund. General revenue would pay Social Security benefits for the next 75 years, then the new fund would reimburse those costs.

“Let’s get it done before it is too late,” said Cassidy, who is running for his third term.

Amid concerns about solvency, some Democrats have proposed minimum benefit increases. Warner said one possibility could be raising benefits for the bottom 20% of workers. That could be a political sweetener for any deal—but it would require more money that needed to simply make the fund solvent.

Sen. Jeff Merkley (D., Ore.), who is running for a fourth term this year, has co-sponsored a bill from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I., Vt.) that would increase minimum benefits and expand the payroll tax to cover high earners and investment income. In his town halls, Merkley said, raising the tax cap is particularly popular.

“We will solve this problem because it has to be solved,” Merkley said. “Even if it is in the ugliest possible fashion at the last second, it will be solved.”

Social Security Fairness Act

Instead of reforming Social Security to make it more solvent, this Congress made Social Security less solvent by extending benefits to the least deserving, that being public unions.

The bill was inappropriately named the Social Security Fairness Act. Cynics may suggest the name was perfect on grounds bills generally do the opposite of their name.

CATO discusses What the Social Security Fairness Act Tells Us About the Likely Future of Social Security Reform

Passing the so-called Social Security Fairness Act sends a clear message about how Washington approaches Social Security reform—and it’s a disturbing one. Congress and President Biden have chosen to ignore all expert advice, cater to organized special interest groups, and burden younger taxpayers with increasingly unaffordable costs.

Instead of sensible policy reforms that better align Social Security benefits with the ability of workers to pay for them, Congress will want to take the path of least resistance. Without significant public pressure to do the right thing, expect a multi-trillion-dollar general revenue transfer (meaning added borrowing) come trust fund depletion, and perhaps superficial fixes like the federal government borrowing money today to ‘invest’ to generate revenue from speculative gains tomorrow.

The Social Security Fairness Act increases the program’s financing gap yet further. Funding this policy with additional payroll taxes would burden 180 million workers with an additional $68 in annual taxes to fund higher benefits for 3 million public sector workers and their spouses by unfairly manipulating the Social Security benefit formula to their advantage. This is a textbook example of Mancur Olson’s theory of collective action, where small, concentrated groups secure disproportionate benefits at the expense of a diffuse majority.

The repeal of the Windfall Elimination Provision and Government Pension Offset creates outsized benefits for workers who had significant earnings that were exempt from payroll taxes compared to those who paid Social Security taxes over their entire careers. For example, economist Larry Kotlikoff highlights a schoolteacher whose lifetime benefits will soar by $830,625 (!) under this law, with her annual retirement benefit more than doubling and her widow’s benefit nearly tripling.

Congressional Republicans’ support for this expensive change likely stems from a political calculation. For a long time, backing the bill seemed like a low-cost way to curry favor with police and firefighter unions, key constituents in many members’ voter base without serious worry that the bill would pass. It took 24 years from when a version of the Social Security Fairness Act was first introduced in 2001 (with a congressional hearing held in 2003) to it being signed by President Biden on January 5, 2025.

The Wall Street Journal suggests the timing—a post-election passage—points to a political payoff for groups like the International Association of Fire Fighters, which lobbied heavily for the measure and declined to endorse Kamala Harris for president (after endorsing Joe Biden in 2020).

If Congress can’t say no to popular and shortsighted benefit increases, how will it tackle the tougher job of making Social Security long-term solvent? The sad truth is that politicians probably won’t even try—at least not until the crisis is too close to ignore.

It’s easy to blame Biden for this but Republicans had to go along or the unfairness act would never would have cleared the Senate.

And as for doing something now, Trump does not want to do anything.

What Will Happen?

A strong possibility is free money. By that I mean no changes other than to guarantee benefits without raising revenue.

Don’t worry. CATO reports the cost would only be $25 trillion over the next 75 years—after taxpayers have repaid the payroll tax surpluses that previous Congress squandered, with interest.

Basically, Congress would simply tell the Treasury to keep selling bonds to finance Social Security benefits, even after the so-called trust fund is depleted.

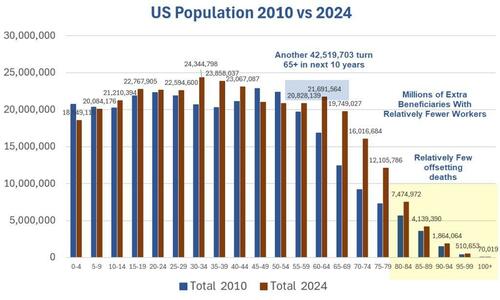

US Population 2010 vs 2024

US Population in 2010 and 2024. Data from Population Pyramid, chart by Mish.

Lasting Until 2032 is Optimistic

Nobody has factored in recession and the accompanying reduction in FICA tax collection.

Insolvency in 5 years would not at all be surprising.